Monsters, pirates, and legends populate the history of New York’s Fire Island. In fact, their stories persist to present day — perhaps because the tales are so larger than life. But what exactly makes this small barrier island at Long Island so welcoming to oversized historical figures? The answer is undoubtedly in its proximity to New York City while maintaining its relative isolation from the rest of the world.

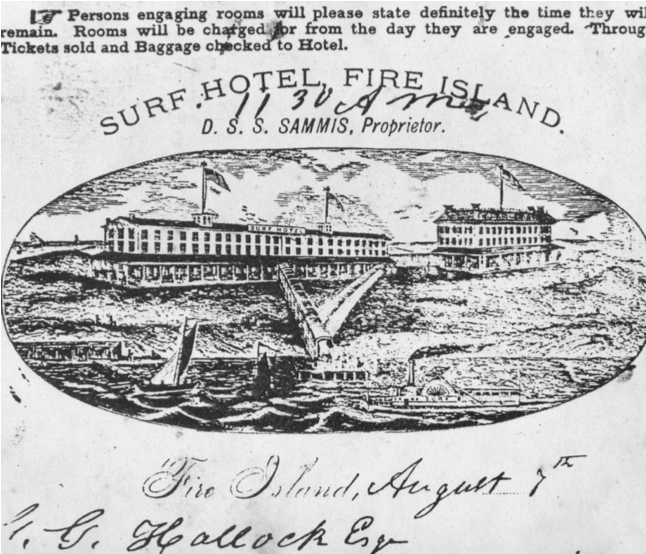

In the seventeenth century, the Dutch settlement of New York and Long Island flourished as sailors, fishermen and traders spread out in all directions from the Hudson River and New York harbor. In fact, the Dutch most likely gave today’s Fire Island Inlet its name — where four small islands are located in the middle of the inlet. In Dutch, the term “Four Islands” (or Fier Eylant) or even “Four Island Inlet” (Fier Eylant Inlaat). Subsequent British settlers no doubt heard “Fire Island.”

The Hapless Pirate

Captain William Kidd didn’t start his esteemed career as a pirate. After his mutinous crew stole his ship in the Caribbean, Kidd went in pursuit of his stolen ship all the way to New York harbor. He dropped anchor there, trying his hand as a married landlubber businessman, but four years later, he decided he had to return to his first love: tracking and killing pirates. With excellent credentials, Kidd was granted a privateering license from the British crown. In 1698, William Kidd and his crew captured the huge and well-armed treasure ship Quedah. The next year, in a strange twist, Kidd and crew were declared pirates by the British government. Fearing capture, Kidd ditched his ship in the West Indies and snuck back to New York in a small boat (along with his loot). Legend has it that Captain Kidd hid his fortune somewhere on Fire Island’s Great South Beach before being apprehended by the British authorities and hanged for his pirating.

“Death of a Once Popular Author”

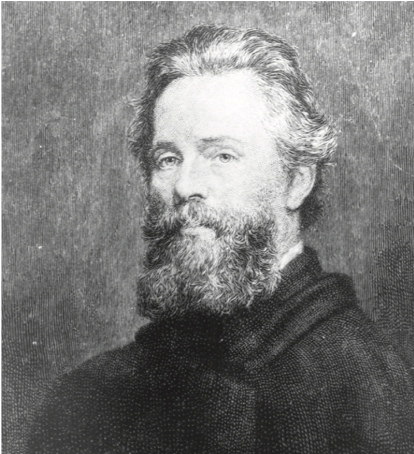

Herman Melville, the world-renowned author of the masterpiece of English literature Moby-Dick, found solace in his finals years visiting Fire Island. Melville was no stranger to sea life. Eighteen months crewing on the whaler Acushnet gave the author plenty of material for novels such as Moby-Dick, Typee, and his final literary triumph Billy Budd. In fact, it was Fire Island that inspired Melville to write once more about moral issues at sea. His allegory is a tale of good and evil where the ship’s captain

Santa Fly-By

Beginning in the 1920s, Santa would fly over Fire Island lighthouses, delivering gifts for coastal families. But why did Father Christmas single out this seaside community? The Fire Island Lighthouse Preservation Society knows why, and they make sure to honor this man and his actions every year. The legend goes that Maine floatplane pilot William Wincapaw, an ace in treacherous weather conditions, would often provide transport for the sick or injured in remote locations, where coastal lighthouses illuminated his path. In 1929, as a sign of his appreciation for their help, Captain Wincapaw delivered Christmas gifts on the isolated island, sometimes dropping gifts straight from his plane. The deliveries were so popular that Wincapaw expanded into Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut, and brought along his son, Bill Jr. The so-called Flying Santas even dressed the part. Over the years, others would fill the role when needed on the flying sled, and the U.S. Coast Guard alleviated costs by providing aircraft for deliveries. The Flying Santa program continued thanks primarily to the members of the Hull Lifesaving Museum, as the era of the lighthouse keeper slowly diminished. Today, Flying Santa supporters work together as the Friends of Flying Santa, Inc. to ensure there would always be sufficient money to keep the Flying Santa tradition alive.

Robert Moses

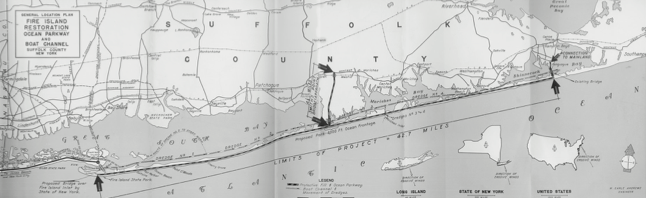

With all these colorful heroes, what would Fire Island be without a villain? Enter Robert Moses. Fire Island is thirty-two-miles long and over a half-mile wide, and is a bonafide natural landmark. The barrier island is a rustic landscape and fragile balance of preservation, one that has been enjoyed by generations of New Yorkers for decades. In the post-war years, so-called “master builder” Robert Moses was empowered by elected officials to help create massive public works projects for New York City and State. Following his success with Jones Beach State Park on Long Island in 1929, Moses sought to develop more of the southern coastline. As the president of the Long Island State Park Commission, he was poised to reach further.

Moses and his wife loved Fire Island. In an effort to bring more New Yorkers to its secluded shores, Moses proposed a four-lane highway connecting Ocean Parkway to Montauk Highway in Montauk. Bolstering his pitch, he felt a highway would enhance the barrier island’s strength in protecting against heavy storms, and roadway height could be a deterrent to flooding stormwater. Following negative newspaper editorials, lawmakers reconsidered the concrete solution over new, filled inlets, and rebuilt natural dunes. Grassroots activism triumphed, but Robert Moses wasn’t finished with plans for Fire Island.

Post-war America saw a boom in suburbia, and Long Island was ground zero for the new experiment in mass single-family home developments. As automobile culture grew in the 1950s, Moses looked for ways to move New Yorkers, and Fire Island seemed perfect for sprawling suburbia. The New York planner got his causeway, even though locals feared large New York City crowds intruding on their day-to-day lives. In 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Fire Island National Seashore Bill, making thirty-three miles of it a national park. Because of, or perhaps in spite of, Moses’s work against a state park, the existing west end park from 1908 was renamed in his honor. Fire Island would remain environmentally and culturally intact.