Barry Farm-Hillsdale was an African-American settlement created on the edge of Washington, DC. The settlement first rose up in 1867, under the auspices of the Freedmen’s Bureau, and its residents continued to fight for racial justice. In fact, in the years after World War II, youth from the community courageously desegregated the Anacostia Pool — a battle that would eventually involve a famous reporter, a Supreme Court Case, and most of all, the brave actions of some Barry Farm-Hillsdale locals.

The first protests

In the summer of 1949, the Department of the Interior controlled six public pools in DC located on federally owned land. In theory, these pools were not segregated. Nevertheless, by custom, the Anacostia, East Potomac, McKinley and Takoma pools were used exclusively by Whites, while the Banneker and Francis pools were used exclusively by Blacks.

On Thursday, June 23, a group of young African Americans from Barry Farm–Hillsdale and Southeast tried to enter the Anacostia Pool without success. They continued trying for the next three days until June 26, when six “Negro youths from 14 to 21 years old were splashed and booed out” of the pool. According to the newspaper reports, between seven hundred and eight hundred Whites of all ages observed the eviction, with fifty of them actively evicting the would-be African American swimmers. Richard Robinson, Carl Contee and Richard Cook, friends and neighbors from Bowen Road, were part of the group evicted from the pool.

Not to be dissuaded, the African American kids returned on June 28. Ben Bradlee, then a young reporter at the Washington Post, described in his memoirs many years later what happened at the pool. Between 3:00 p.m. and 6:00 p.m., Whites and African Americans battled in the area around the swimming pool. Mounted park police rode their horses, trying to keep the two factions away from each other. Both sides were armed with clubs, and some of these clubs had nails sticking out of them. Bradlee and a colleague covered the event and filed the story, sure that it would appear in the paper the next day. The Post, to the disappointment and indignation of the young reporter, did not pick up the story.

Things heat up

The attempt to desegregate the Anacostia Pool continued on June 29, with violent clashes between hundreds of Whites and African Americans. Some of the Whites were members of Henry A. Wallace’s Progressive Party and were there to demonstrate against segregation and distribute handbills urging the desegregation of the Washington, DC pools. Everett McKenzie also remembered that his younger brother, Eugene (whose nickname was “Mann”), and Clarence “Dusty” Prue were there. James Chester Jennings Jr., also present, remembered that the Anderson brothers—Otis, Thomas and Bill—were part of the crowd. Toussaint Pierce, who had attended the West Virginia State College the previous year, had come to the pool to swim but found that it was already closed. He was then attacked by a White youth who threw a stone at him. Then a park police officer ran him down on a horse. When Pierce picked up a rock to throw back, the police officer grabbed him and took him to the Eleventh Precinct. Pierce was kept for an hour until his father came to pay his five-dollar bail.

At the end of the demonstration, Everett and his brother were so afraid that they decided to head back home by following the railroad tracks that ran in front of the pool and went into the Barry Farm–Hillsdale neighborhood. That was the long way to get home instead of coming out through the usual route of Good Hope Road and Nichols Avenue, which would take them through White Anacostia. Otherwise, they might have been the victims of a car driven by a White man who was accused of trying to run down an African American youth at the entrance to the park. More violence occurred on Nichols Avenue when African American youths taking that route back home jostled and frightened a White girl, who then took shelter at a grocery store located on the 1900 block.

Slow solutions

The solution for the rioting was to close the Anacostia Pool. Washington, DC organizations divided into two groups: those proposing the reopening of the pool on a desegregated basis and those adamantly against it.

A sensible group of twenty-five White and African American mothers sent a letter to Interior Secretary J.A. Krug stating that they expected “‘determined enforcement’ of Interior’s nonsegregation [sic] policy” at the Anacostia Pool, with the provision of adequate policing by White and African American policemen.

In March 1950, the Interior Department decreed that all of its six swimming pools in Washington would reopen “on a non-segregated basis.” The Anacostia Pool opened on June 24, 1950, without incident. By October, after the end of the swimming season, integration of the pools was well established, but it was considered both a success and a failure.

It was a success because there were no violent incidents. It was a failure because the attendance of Whites dropped considerably. At the Anacostia Pool, the attendance was now 90 percent African American. Desegregation of the swimming pools did not determine the desegregation of all recreational facilities in the nation’s capital. Actually, in White Anacostia, it created so much distress that the Anacostia Citizens Association withdrew its request for the creation of a playground in the neighborhood. The stated reason was that the residents feared that eventually the playground would be integrated and there would be trouble like with what happened at the Anacostia Pool.

On March 18, 1954 the day following the Supreme Court decision on school segregation, the District of Columbia Recreation Board integrated all the recreational facilities in the city. It was almost five years to the date when the fearless youth from Barry Farm–Hillsdale had faced segregation head-on and integrated the Anacostia Pool by force.

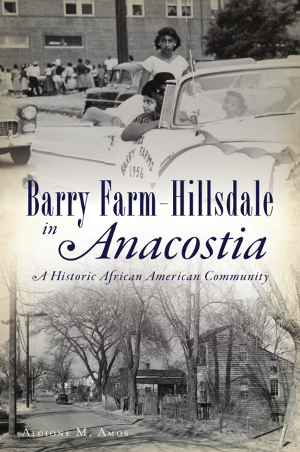

Barry Farm–Hillsdale was created under the auspices of the Freedmen’s Bureau in 1867 in what was then the outskirts of the nation’s capital. Residents built churches and schools, and the community became successful. In the 1940s, youth from the community courageously desegregated the Anacostia Pool, and Barry Farm Dwellings was built to house war workers. In the 1950s, community parents joined the fight to desegregate schools in Washington, D.C., as local leaders fought off plans to redevelop the area. Both the women and the youth of Barry Farm Dwellings, then public housing, were at the forefront of the fight to improve their lives and those of their neighbors in the 1960s, but community identity was being subsumed into the larger Anacostia neighborhood. Curator and historian Alcione M. Amos tells these little-remembered stories.