In the early 20th century, swing music was the most popular genre amongst listeners, and hundreds flocked to dance halls across the country to hear big bands led by the likes of Duke Ellington and Artie Shaw. But after World War II, it seemed swing had met its end, as singers began to take over the music scene. From a tax on admission to Rock ‘n’ Roll, here are the biggest theories on what truly ended the Swing Era.

The Swing Era

During the decades of the 1920s, 30s, and 40s, jazz dominated the American music scene. Big bands, led by bandleaders like Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, and Artie Shaw, became nationwide sensations for their orchestras, which typically played swing music. Swing, a derivative of 1920s jazz, was popular for its emphasis on off-beat tempos, which lent well to dancing. These bands would typically feature soloists who led dance numbers, including musicians like Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday.

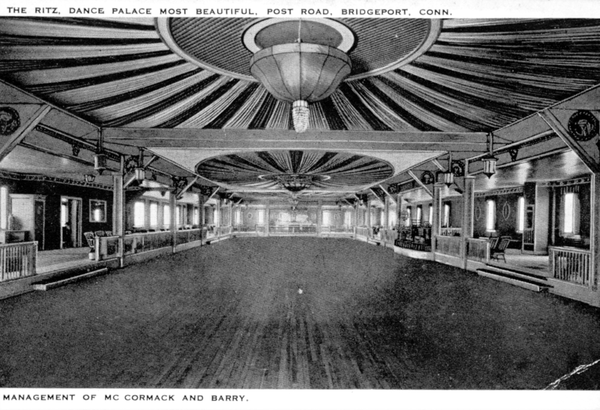

By 1936, swing had become the most popular genre of music in the United States, as young Americans filled dancehalls across the country. Clubs like the Ritz Ballroom in Bridgeport, and the Cotton Club in Harlem, became increasingly popular. Many of these nightclubs would combine music and dancing with dinner, giving an all-inclusive experience out for patrons. However, by the end of World War II, swing clubs had begun to die out, and by the late 1940s Americans had moved forward from their big band obsession in favor of newer genres like Bebop and Rock ‘n’ Roll.

The Theories

Many different ideas have been presented on why the popularity of big band and swing began to wane, ranging from federal taxes, to a willful decline:

- The Cabaret Tax: In an effort to fund wartime endeavors, the US government passed the cabaret tax in 1944. The tax, which was levied against any “public place where music and dancing privileges… except instrumental or mechanical music alone, are afforded the patrons in connection with the serving or selling of food, refreshment, or merchandise,” took 30% of the gross receipts from clubs. This action hobbled swing nightclubs, who struggled to afford traditional big bands. In the interest of cutting costs, clubs began employing smaller bands, rather than paying for larger orchestras. As a result, music forms like Bebop came to the forefront, while big band fell to the wayside.

- World War II: When the US joined the Allies in World War II, swing was at the height of its popularity. As a result, it was often used as a morale booster for troops, with many soldiers forming their own orchestras. The most famous of these was led by bandleader Glenn Miller, who was commissioned as a captain in the US Army in 1942. Miller’s 45-piece orchestra toured the world entertaining troops throughout the European Theater. However, by the end of the war, many American were looking to move forward from what was viewed as an extremely painful time in history. Big band music served as a major reminder of the war, and the decade preceding it. Consequently, the popularity of big band and swing music began to decline as the American public tried to distance themselves from memories of war.

- The Musician Strike of 1942: In late 1942, the American Federation of Musicians called the longest strike in entertainment history against major US recording companies over royalty concerns. This strike, which lasted two years, forbid members of the union from making commercials recordings for record companies. The vast majority of union members belonged to big band orchestras, who subsequently did not release new material for a rather substantial time period. However, singers like Frank Sinatra (who were not included in the strike) quickly rose to prominence during this time period, as record companies began to focus on vocalists, rather than supporting bands. Prior to this strike, vocalists had been the support to orchestras, rather than vice versa.

- Self-Implosion: While swing was the most popular form of jazz, many of the era’s biggest bandleaders did not actually want to record dance music. Often, bandleaders wanted to perform jazz music that people would sit and seriously listen to, in a similar vein to classical music. When it was evident this bridge from dance to more sober music wouldn’t occur, many bandleaders left the profession. Artie Shaw, who led some of the most popular bands of the era (and sold millions of records) left big band at the height of his popularity, later disdainfully citing that all people wanted to hear “was dance music.”

- Rock ‘n’ Roll: Another popular theory is that as the children of the Big Band era reached their teenage years and young adulthood, many wanted to rebel against their swing-loving parents. As a result, rock ‘n’ roll began to gain traction in the mid-1950s, as legends like Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly began their careers. Rock ‘n’ roll went on to be the predominate genre of the mid-to-late 1950s, setting the foundation for the explosion of the rock genre that began with The Beatles in the early 1960s.

So what’s the truth?

The death of the Swing era can’t be attributed to any one factor: it could have been for any combination of these influences, or perhaps all of them. Today, the Jazz industry has been on a steady decline – currently, less than 2% of US music sales are from the jazz genre, and nearly half of these belong to artist Kenny G. However, swing has been preserved by a large amount of revivalists, who attempt to keep the tradition of the Big Band era alive. Nightclubs like the Swing 46 in New York City, or Maxwell DeMille’s Cicada Club in Los Angeles host dinner and dancing à la the 1930s and 40s, while swing dance groups and classes can still be found in cities nationwide. While the time of Duke Ellington, Glenn Miller, and their contemporaries has passed, they have left an undeniable influence on American music history, and are preserved through memory and tradition.