How could a history of a cruiser, even one named for Houston, be part of local Houston history? US cities have had US Navy warships named after them almost as long as there has been a United States Navy, from the frigate Boston in 1799 through the newly commissioning littoral combat ship Little Rock. Yet no city has had as intense a relationship with a namesake ship as the city of Houston did with the first cruiser Houston.

It was the first warship named for the city of Houston, but it was not the first US Navy vessel named for Houston. The German freighter Leibenfels was trapped in the United States when World War I started. When the US entered the war, it was seized. Commissioned as Houston, it served as a fleet auxiliary during World War I, and was sold in 1922.

That ship failed to project the image Houston desired. In the 1920s, Houston was at the start of a boom that ran for the rest of the century. It would double in size during that decade, growing to nearly 250,000 people by the end of the decade. Houston wanted a naval ship named for the city which fit the city’s reputation – fast and powerful.

When the Navy announced plans to build a new series of cruisers –named for cities – Houston decided one of them would be the perfect ship to bear the city’s name.

Texan Persistence Pays Off

Texans are not known for their retiring nature, especially Houstonians. Rather than chance the Navy’s naming the cruiser for a less deserving city, Houstonians lobbied the Navy to name one of the six new cruisers for the Bayou City. Everyone from Texas’s governor to Houston schoolkids wrote in. On September 1, 1927, after a nine-month siege, the Navy surrendered, announcing the fifth Northampton-class cruiser would be named Houston.

The ship was a beauty when completed. It had an extended forecastle so it could serve as a flagship, and space for extra officers’ cabins. The extended forecastle, a clipper bow, and clean superstructure arrangement yielded lines which pleased the eye.

The ship was launched at the peak of the Roaring Twenties, but by the time it was commissioned, the nation was in the grip of the Great Depression. To Houston, its cruiser was a reminder of the good days when it was launched.

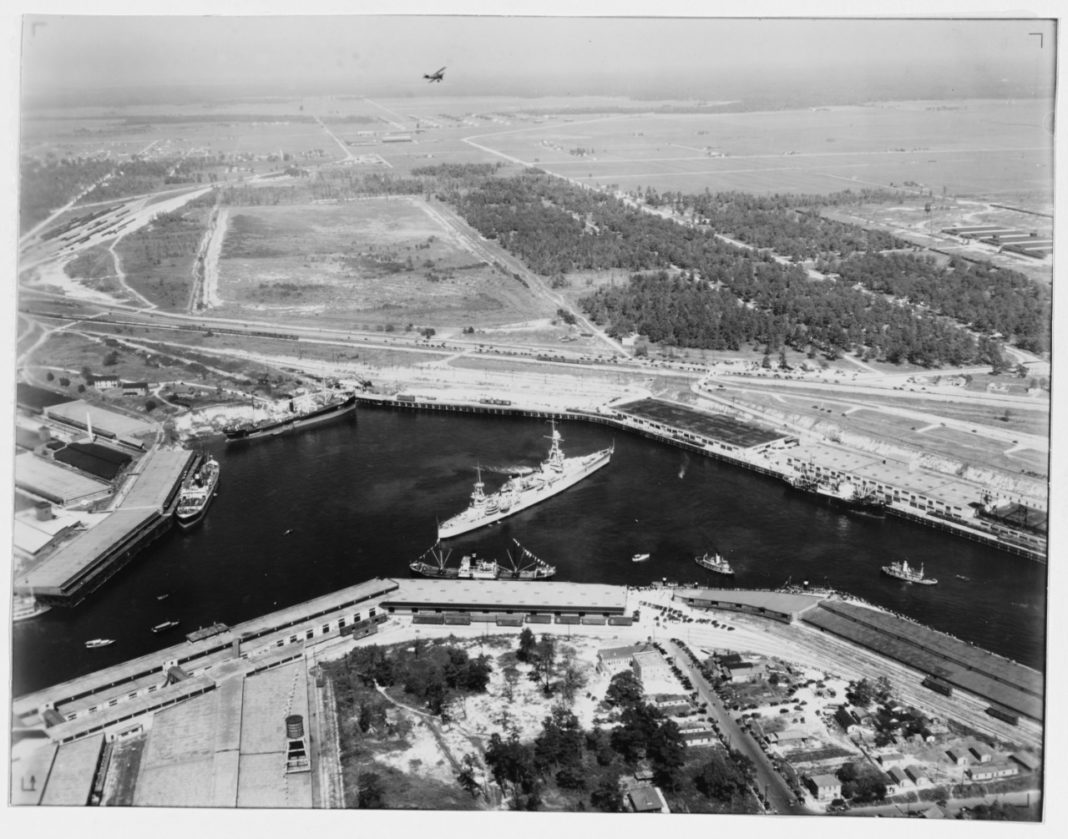

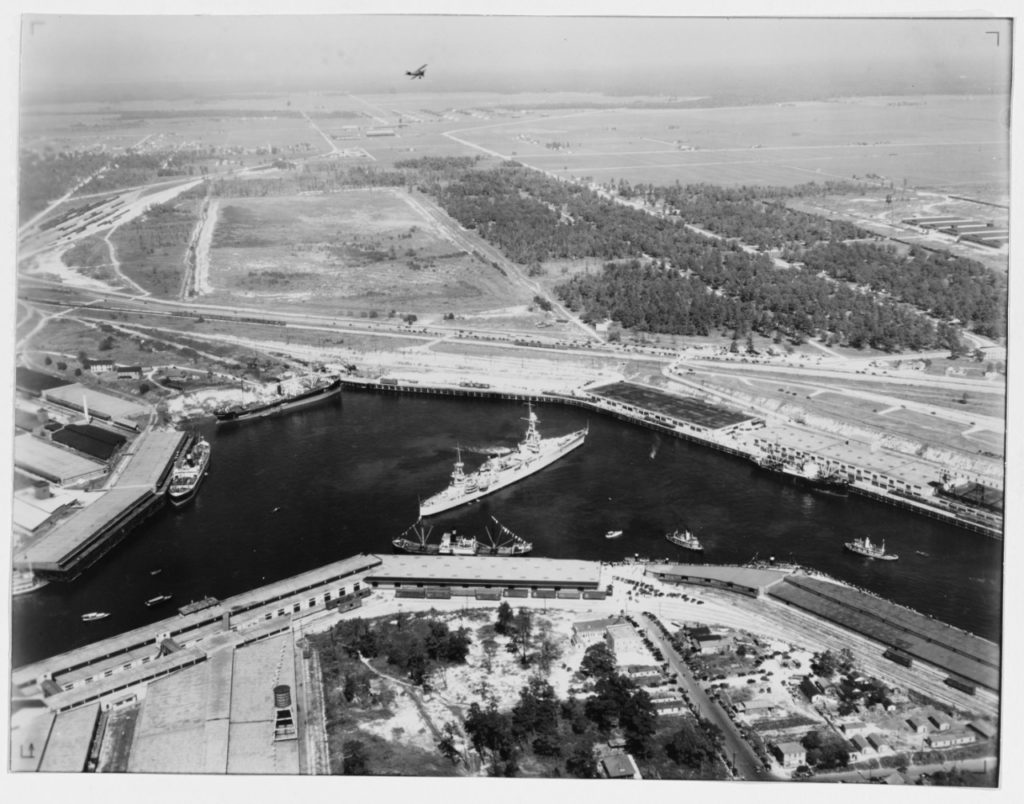

When the Houston visited the city for which it was named for the first time, the city went wild. Over 100,000 visitors toured the ship when it anchored in the Port of Houston Turning Basin in October 1930. The city also presented its cruiser with a silver service.

It was the first of an ever-growing list of gifts showered on the cruiser Houston by the city of Houston. Houston would only visit its namesake three more times during its brief life, but the city treated the ship like a beloved yet far-off son. Houston received everything from Christmas fruitcakes to a piano from the city over the next decade.

A Source of Pride

Houston had reasons to be proud of its cruiser. Houston served as flagship of the Asiatic Fleet twice. It served as President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s flagship on four occasions. The President spent extended “inspection tours” (actually vacations) aboard Houston in the 1930s.

Houston was on its second tour as Asiatic Fleet flagship when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, plunging the United States into World War II. Stationed in the Philippines, Houston led an outnumbered and outgunned collection of US warships against the powerful Imperial Japanese Navy.

For three months Houstonians followed the exploits of Houston as the cruiser battled against overwhelming odds. Then, after the disastrous Allied loss at the Battle of the Java Sea, Houston disappeared. It survived the battle, but failed to arrive at Australia after being ordered out of the Java Sea. For three months after it last radioed Australia, Houston was missing, presumed lost. Not until July did Japan notify the world it sank Houston during a midnight battle on March 1, 1942.

A Worthy Replacement

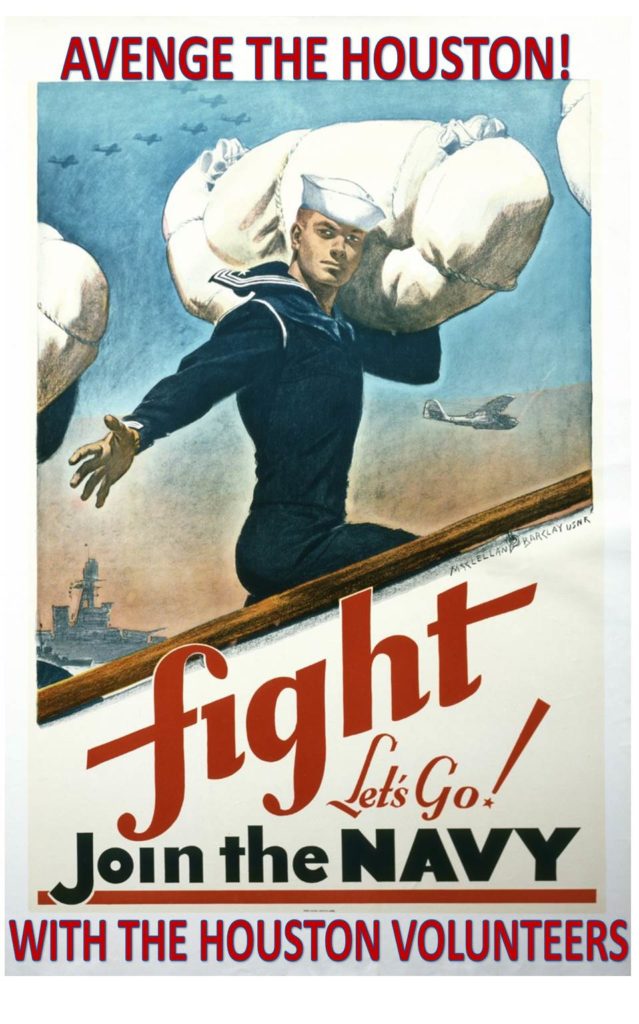

The city’s connection with its namesake cruiser was never clearer than after the cruiser’s disappearance. Houston held a recruiting drive to replace the 1000-man crew lost with the ship. During the 60 day enlistment drive, 1650 men from Houston volunteered for the Navy. The first 1,000 to sign up were honored as the Houston Volunteers, participating in a swearing-in ceremony conducted by Rear-Admiral William Glassford, the last man who used Houston as a flagship.

The city sponsored a war bond drive to pay to replace the lost ship with a new cruiser. The drive raised enough money to pay for a new light cruiser named Houston, and to pay for an aircraft carrier. The aircraft carrier, named San Jacinto (for a Texas Revolution battle fought just east of Houston) was a light carrier, built on a cruiser hull.

Both ships fought with distinction against Japan during World War II. One pilot in San Jacinto’s carrier group was a young man from Connecticut who moved to Texas after the war, where he later entered politics. Eventually he became the country’s 41st President: George H. W. Bush. He lives in Houston today.

Nor did Houston forget the first cruiser Houston after World War II. The University of Houston became the home of a major collection of artifact and archives from USS Houston. It has everything from a collection of the cruiser’s newsletter (The Bluebonnet) to photographs and memorabilia contributed by Houston survivors and their families. It also has Houston’s first bell on display.

In 1998 the USS Houston Monument was erected in Sam Houston Park in downtown Houston. A granite obelisk, it is topped with the brass bell aboard Houston when it sank at the Battle of Sunda Strait on March 1, 1942. A memorial service for those who died aboard Houston is held annually there.

Seventy-five years after it sank, the Bayou City still remembers the cruiser Houston. Find out more about this love affair in The Cruiser Houston.

Learn More: Buy the Book!

This post was written by author Mark Lardas for The Cruiser Houston (Arcadia Publishing)