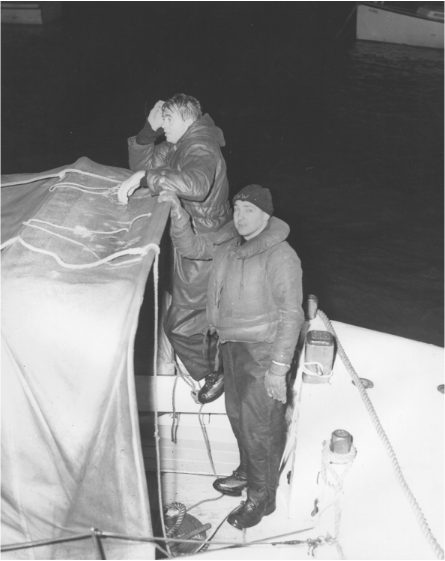

The four young Coast Guardsmen barely spoke. It was February 18, 1952, and they were driving from the Chatham Lifeboat Station to the fish pier across town.

Ervin Maske, Andy Fitzgerald, Richard Livesey and Bernie Webber were about to head into the fist of a New England nor’easter, the winter storm mariners fear most because of its high winds and cold. This particular nor’easter would be one for the history books: up to thirty inches of snow fell across the region between February 17 and 18.

Only a trace of daylight was left of that miserable day when the four- man crew pulled up to the pier. Their mission–to successfully rescue the SS Pendleton, a large tanker the storm had snapped in half–has become famous among maritime buffs. But before they could save the ship, the crew had to reach the ship–and that is itself an inspiring and terrifying true life story.

Fearful from the beginning

The crew’s orders that February day came from an inexperienced officer in charge, Daniel Cluff, who’d barely set toes in salt water: locate the 503-foot oil tanker Pendleton that had split in two off Chatham, at the elbow of Cape Cod, and was in imminent danger of sinking, possibly with human lives at stake. Under normal conditions, Coast Guard crews train for hundreds of hours before this type of mission, but that evening Bernie had orders to cobble together a crew and search for the Pendleton, so for the first time these untested partners would venture out together.

On the dock, Bernie ran into John Stello, a friend and local fisherman. “Call [my wife] and let her know what’s going on,” Bernie asked him. “You guys better get lost before you get too far out,” Stello shouted.

Stello’s meaning was clear: “go hide somewhere until the storm passes or else you’ll die.”

Crossing the bar

They crew climbed into a dory and rowed to where the CG36500, a thirty-six-foot motor lifeboat, was moored. It took only a few minutes to get underway: unfasten lines to the anchor; fire up the ninety horse power gasoline diesel engine; and check the throttle. Daylight had slid into night.

Onward they went, past the red blinking light of the buoy that marked the entrance to Old Harbor, the last shred of technology wedged into the waves. Approaching the notorious and dynamic Chatham Bar, the crew began to sing Rock of Ages, a favorite of Ervin’s, and Harbor Lights. The storm muffled their voices.050.8 Pendleton Disaster.indd

Crossing the bar sent shallow but thick waves smashing against the motor lifeboat, throwing the vessel high in the air to land on its side in the valley between two waves. The boat was designed to self-right, thanks to a hull of two thousand pounds of steel, and was quickly smote. Topside, a wave smashed the windshield, sending glass into the seas and ripping the compass from its mount. Webber struggled to regain control of the CG36500 and steer into the waves. Finally, the waves had increased— and so had their height—and Bernie knew by this time he had crossed the bar.

Finding the SS Pendleton

Every so often the lifeboat’s engine would conk out when waves rolled the CG36500 over and the ninety horse power gasoline diesel engine lost its prime. When that happened, Engineer Fitzgerald crawled into the cramped compartment and restarted the engine.

The crew continued to search. Finally Bernie sensed something was there. Years later, the memory of that eerie sensation would send chills through his body. “I had a crewman go forward and turn on the searchlight,” Bernie recounted. “Also, one could hear a hissing sound,” from the Pendleton, Bernie said, “almost like a screeching, hissing sound. I think it was every time it went down into the sea with all the metal hanging off it, it created this noise. Very hard to explain, but I just knew something was there.”

The CG36500 and its brave crew had found the SS Pendleton. Now they had to save it . . .