When systemic racism tried to stop them, South Bend residents built a “nice neighborhood” for themselves.

You may have heard that South Bend’s mayor is running for president. With Mayor Pete in the news, the city’s past is getting lots of attention. Pete Buttigieg’s record on racial issues has been criticized, but South Bend has some bright spots too—even if they come from an earlier and often overlooked era.

During the 1950s, South Bend (and most cities in America) featured a harsh environment of discrimination and exclusion for its African American residents. One way this occurred was through real estate and lending policies that made it hard for those residents to buy nice homes in mostly white neighborhoods.

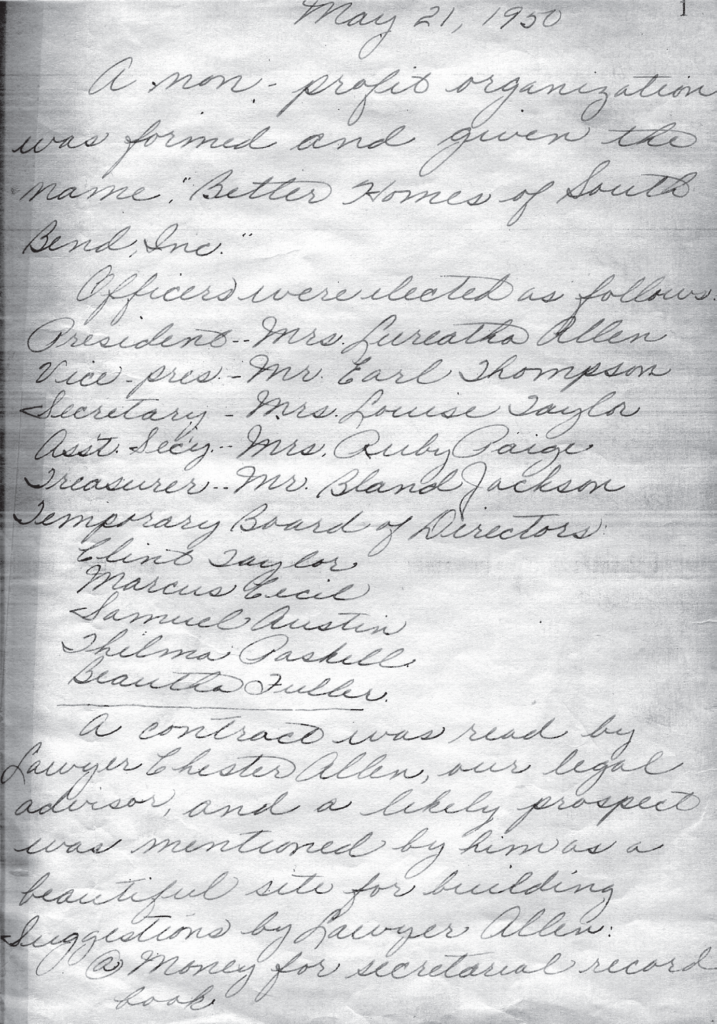

But on a Sunday afternoon—May 21, 1950—a group of South Bend locals came together to work on making their dream become reality. Many of them were associated with the local Studebaker factory. They formed a nonprofit and called it The Better Homes, a title that summed up the group’s endeavor. Its members desired nothing more than to own their own homes “in a nice neighborhood,” as one of them characterized it. The name echoed the popular book Better Homes at Lower Cost and the Better Homes and Gardens magazine.

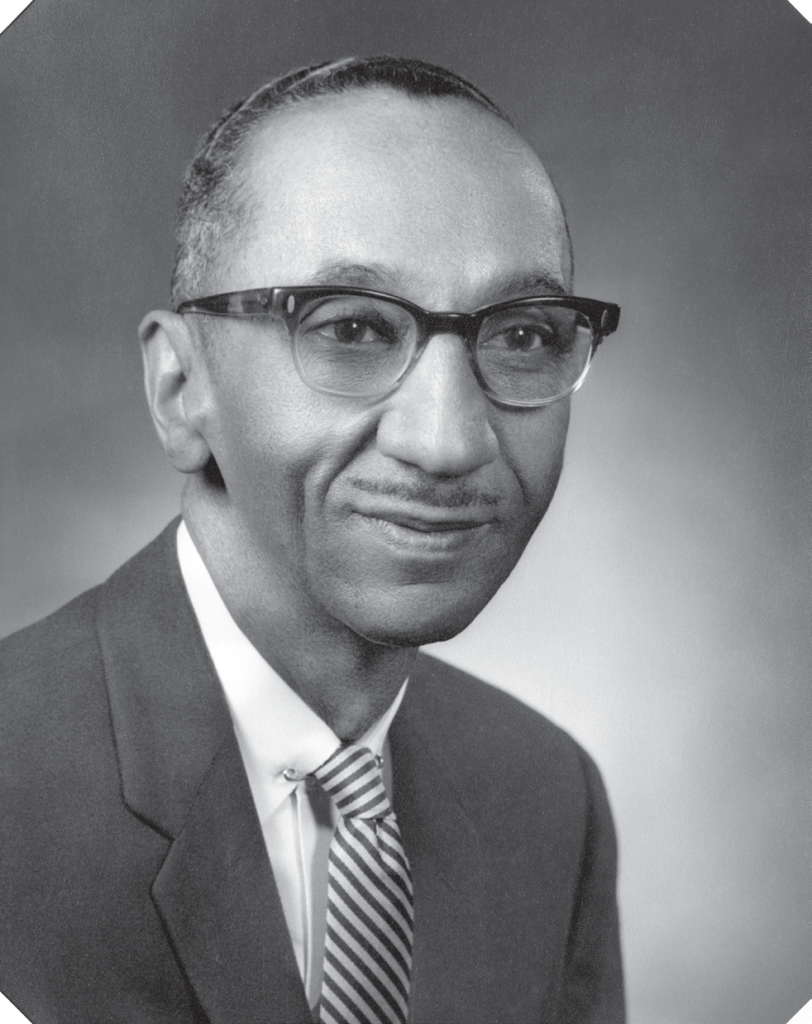

That Sunday meeting was a secret. The group’s attorney, J. Chester Allen, wanted them to move quickly and secure the site before anyone was alerted to African Americans moving into a hitherto white neighborhood. He stressed the importance of acting as a corporation, which would give them a better chance at success than if they were just a group of individual families.

They knew it would be a struggle. As the Reverend Buford Gordon had written in his 1922 book The Negro in South Bend, “There are people who think that the Negro is in the same environment that the white man is, since they are living side by side in a city. They are not.”

Better Homes bought the land to build new houses, at first in the North Elmer Street area, but the white residents did not like the prospect of a group of African Americans moving into their neighborhood. This, at least, is the assessment of Nola Allen, who heard about the difficulties from her mother. In Nola’s opinion, “Getting the land was the easiest part, but after that nothing was easy. Nobody wanted them to build on that land.”

They ran into problems finding a good contractor. One popular company was known to build nice homes for white families on the south side of Western Avenue and cheaper ones for African Americans on the north. They ran into problems connecting to South Bend’s sewer system.

They ran into problems finding financing. In November 1951, Lureatha Allen at last could report to Better Homes that permanent financing had been secured under 203, the HUD Basic Home Mortgage Loan 203 (b).

But they worked together, using a co-op model, the few legal protections available to them, and a lot of hard work and community spirit. Slowly the houses were built.

Leroy and Margaret Cobb, to take one example, moved into 1702 North Elmer Street on Saturday, November 1, 1953, over three years after that first secret meeting of Better Homes. The date is etched in Leroy’s mind. “I was elated.”

They now had plenty of space for their growing family. Their third child was to be born in a couple months. And here Leroy was, only twenty-three years old, and he owned his own brand-new home in a nice neighborhood. He often thought of others in their group who, although much older, had never had a home of their own before this. His grandmother on his mother’s side often told him: “You don’t know how fortunate you are. I’ve never owned a home.”