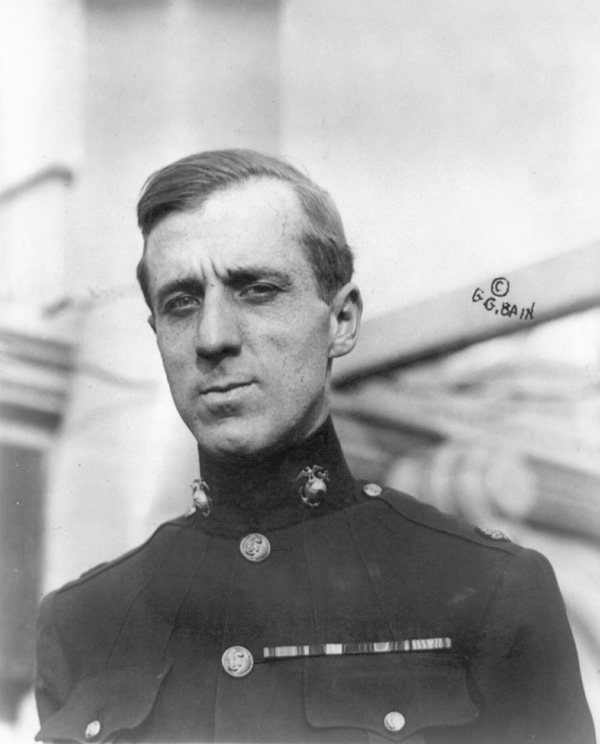

In 1934, a colossal claim reached the American news media: There had been a plot to overthrow President Franklin D. Roosevelt, in favor of a fascist government. Supposedly in the works since 1933, the claims of the conspiracy came from a very conspicuous and reliable source: Major General Smedley Butler, one of the most decorated war heroes of his time.

Even more unbelievable were his claims of who was involved in the plot – respected names like Robert Sterling Clark, Grayson M.P. Murphy, and Prescott Bush. While news media at the time mocked Butler’s story, recently discovered archives have revealed the truth behind Major General Butler’s claims.

Who was Smedley Butler?

Born in 1881, Major General Smedley Butler was the eldest son of a Quaker family from West Chester, Pennsylvania. Butler came from a line of civil-serviceman: his father, Thomas Butler, was a representative for the state of Pennsylvania in Congress, and his maternal grandfather, Smedley Darlington, was also a Republican congressman.

Butler served in several major world conflicts, including the Spanish-American War, the Philippine-American War, the Boxer Rebellion, and World War I. During his time in service, Butler became known for his bravery and relentless leadership in battle, and he was rewarded with several distinctions, including multiple Medals of Honor, an Army Distinguished Service Medal, the Marine Corps Brevet Medal, and a Navy Distinguished Service Medal.

In total, Butler served for 34 years in the Marine Corps, and earned 16 medals for his time in service. He is currently the most decorated Marine veteran of all time. He died in 1940 at the age of 58.

The Business Plot

After leaving the service, Butler held many roles, but became best-known for his activism. Butler’s various accolades made him a household name following World War I, and he was well-known among veteran circles as a champion of veterans’ rights. This included supporting the so-called Bonus Army, a large group of veterans and veteran supporters who lobbied Congress for payments of bonds issued to veterans prior to the war.

This positive public image, and demonstrated ability to rally people under his leadership, were perhaps the reason why Butler was approached by Gerald C. MacGuire and Bob Doyle in 1933. MacGuire, a bond salesman, and Doyle were members of the American Legion, an organization meant to support veteran rights and opportunities.

During their first meeting with Butler, MacGuire and Doyle asked the Major General to speak at a Legion convention in Chicago, claiming they wanted to point out the various problems with the Legion’s leadership. Butler was at first open to this idea, knowing that the Legion had several administrative issues that ultimately compromised veteran benefits.

However, over subsequent meetings with the two men, Butler quickly began to suspect that something was amiss – during their second meeting, MacGuire showed Butler bank statements amounting to over $100,000 USD (valued at nearly $2 million today), which he hoped Butler would use to bring veteran supporters to the convention. The Major General was stunned: there was very little chance that a group of veterans had been able to gather such a vast amount of funds. Even worse was the speech that MacGuire asked Butler to deliver – a speech which had little to do with veteran affairs, and instead was more critical of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s recent move away from the gold standard.

The abandonment of the gold standard was a major sticking point for many high-ranking officials and bankers in the country during 1933. Although there were several recognized issues with money backed by gold (such as dependency on gold production, and short-term price instabilities), many bankers were fearful that their gold-backed loans would not be paid back in full by the President’s new policies.

The departure from the gold standard just added to other concerns about FDR’s policies, particularly his plans to provide subsidizations and jobs for the poor, which businessmen and conservative politicians alike took as an indication of Roosevelt’s socialist leanings, or (even worse) a communist. Butler could sense this disgruntlement when he asked to meet with MacGuire’s superior, and found himself speaking with Robert Sterling Clark, an heir to the Singer Sewing fortune. Clark was much more upfront than MacGuire, telling Butler that his real interest was in preserving the gold standard, even claiming that he “had $30 million, and was willing to spend half of the $30 million to save the other half.”

Butler, true to his patriotic form, flatly refused the offer to deliver the speech at the convention in Chicago. After parting ways with MacGuire and Clark, he heard little from the men until MacGuire began travelling through Europe on a trip funded by Clark. MacGuire began sending postcards to Butler from various European locations, including Italy, Germany, and France.

Upon returning to the States, MacGuire called another meeting with Butler, where he was much more transparent about his plans: Admitting that the money he had gathered came mostly from captains of industry, MacGuire told Butler that he had travelled Europe to see how veterans operated within foreign governments. After discounting the governments of Germany and Italy, he described a facet of French government which was run quite well by veterans.

These various observations led MacGuire to believe that the only way to save the country from FDR’s “ill-fated” policies was to create a military state run by former servicemen, with Roosevelt serving as a figurehead, rather than a true leader. Butler asked what MacGuire wanted from him, and was told he would be the ideal leader of these veterans, promising him an army of 500,000 men and financial backing from an assortment of rich businessmen, so long as he would be willing to lead a peaceful march on the White House to displace Roosevelt.

The McCormack-Dickstein Committee Investigation

Astonished by MacGuire’s plans, Butler knew he would need someone to corroborate his story if he was going to stop the intended coup. Having previously worked as the police captain of Philadelphia, Butler reached out to Philadelphia Record writer Paul Comly French, who agreed to meet with MacGuire as well. During this meeting, MacGuire told French that he believed a fascist state was the only answer for America, and that Smedley was the “ideal leader” because he “could organize one million men overnight.”

Armed with French’s mutual testimony, Butler appeared before the McCormack-Dickstein congressional committee, also known as the Special Committee on Un-American Activities, to reveal what he knew about the plot to seize the presidency in November 1934. The committee at first discounted a large part of Butler’s testimony (even writing in their initial report that they saw no reason to subpoena men like John W. Davis, a former presidential hopeful, or Thomas W. Lamont, a partner with J.P. Morgan & Company).

However, with the testimony of French, and the erratic testimony of MacGuire, the committee began to further investigate the plot. The final reports of the committee sang a different tune, finding that all of Butler’s claims could be corroborated as factual. However, they also stressed that the plot was far from being enacted, and it was not clear if the plans would have ever truly come to fruition.

Quickly becoming known as the “White House Coup” and “Wall Street Putsch,” many major news sources derided Butler’s claims, as the committee’s final report was not made available publicly. Those implicated, ranging from the DuPont family to Prescott Bush, the grandfather of future President George W. Bush, laughed off Butler’s claims. Evidence of the validity of Butler’s testimony was not released until the 21st century, when the committee’s papers were published in the Public Domain. No one was ever prosecuted in connection to the plot.

Butler, for his part, went on to continue advocating for veterans. He also became a staunch opponent of capitalism, which he felt fed war efforts. His views were published in his well-known short book War is a Racket, which was published in 1935. There’s no telling how far the plot to overthrow the President may have gone without Butler’s intervention, but one thing is certain: its failure was the work of one patriotic Major General, and his life-long love of democracy.