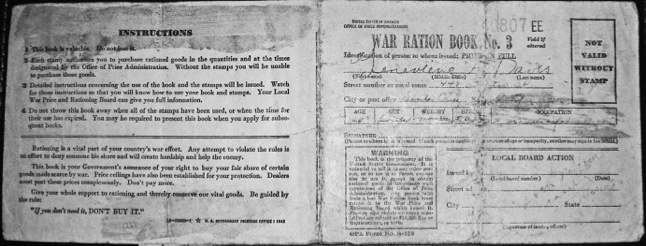

Rationing and food shortages had a huge impact on the average citizen and upon the restaurant business in Santa Cruz County during the 1940s. The lives of restaurant owners and their employees were significantly changed and forever interrupted by World War II; either they joined the service, remained at home, or turned to jobs where the work was going towards the war effort. Several people who lived through these war years shared with me their recollections of food rationing and ration books and the changes to everyday home life. Restaurant owners in Santa Cruz County, in addition to coping with rationing of food supplies for their businesses and the decrease in tourism, were now officially required to maintain their prices at a fair rate and to post this information on site.

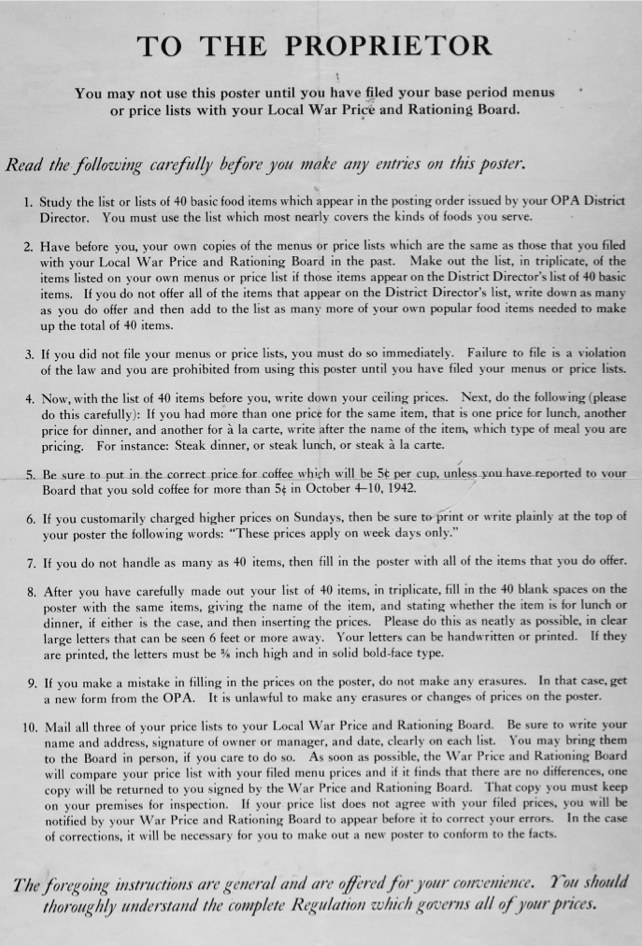

The Office of Price Administration [OPA] imposed a strict rationing policy for restaurant operators: they were to document the number of meals served during the month of December 1942. This number would then determine what the restaurant could charge as their “ceiling price” for the next year. But if these figures were considered too low, or incorrect, the restaurant owner had to fill out a form to explain why and then petition to the local board for a price increase. In tourist towns like Santa Cruz, CA, for instance, the data for December would naturally be different from the data of sales in July, because the summer months reflected the height of the tourist season. Regardless, the OPA certifications were required to be posted in plain sight and also printed on the newly revised menu. Intact OPA posters detailing the rules for each restaurant owner are quite rare.

Institutions such as restaurants, hotels, and hospitals were instructed to apply for their ration books at the high schools. Restaurants were issued between 20-30% more of an allotment of ration coupons than private citizens for sugar, flour, processed foods, canned goods, and meat. Receiving more sugar, flour, and

Many women took on the responsibility of running the family restaurant business while their husbands, sons, and uncles were serving in the military. Or, as the Tea Cup co-owner Rose Yee did (Dan Y. Yee’s wife) – simply close the restaurant temporarily, putting their business on hold until her husband came back from the Army (he returned in 1946). Women were in charge of managing ration coupons, ordering supplies, stocking groceries, keeping the accounts, paying bills, hiring new employees (if possible) and, in general, having to “make do.” Restaurant owners had to repair old equipment like gas ranges and range boilers; any plans for an upgrade to a newer model were put on hold until the war was over. Citing Spiegel Catalog. Chicago: 1943, page 199; “The sale of plumbing equipment, gas ranges, and heating equipment including gas, oil, coal and wood heaters is restricted by government order.”

There was an itemized application describing the “Definition of Emergency Repairs necessary to maintain minimum heating and sanitary conditions required for public health. These remedial repairs are necessary because of the imminent breakdown of plumbing or heating equipment which is worn out or damaged beyond repair.” This meant if the repairman could not, for example, fix the damaged gas line or water pipe, then the restaurant had to explain why each repair was impractical and itemize the equipment to be removed. These restrictions were accepted with the phrases “We’re making the best of the situation,” and “We all have to manage until this war is over.”

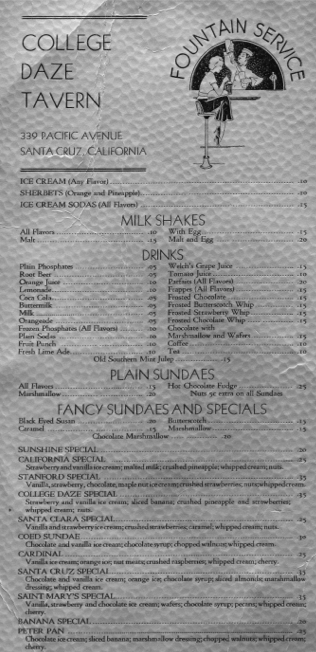

Restaurant menus went through a radical design change during the rationing years. The Art Deco menu designs of the 1920s and 1930s with their fancy highlights of gold and glitter were now a thing of the past. In contrast, menus designed for use in the war years were printed on an inexpensive quality of paper. Paper mills were currently doing war work assignments and former mill workers and shop printers may have been drafted. Per local historian Judy Steen; “Polk’s Santa Cruz Directories for 1942–1945 are missing either because of self-imposed paper shortages or due to security reasons because of its location, being a coastal city during WWII.”

The printers used the same cheap pulp paper used for the mass printing in Armed Services Editions of popular novels that were sent to the men and women in uniform. The menus had fewer pages; most often these menus were just the covers with the selections on the inside and then on the back a list of cocktails. A patriotic quote of “Buy War Bonds” was sometimes printed on an inside corner. If there was a daily special, there was a small piece of paper, perhaps handwritten, attached with a paperclip or straight pin or stapled. Glossy or fancy outer covers were unavailable and unattainable.

Due to a nationwide shortage of meat (meat was going to the troops), the OPA declared that Tuesdays, as well as Fridays, also be “meatless.” Since there was less meat, the menu might list a lamb stew rather than a lamb chop, beef stroganoff instead of a steak, and promoted a variety of different vegetables. On June 30, 1943, the Santa Cruz Sentinel reported, “Meat Market Shelves Bare. At noon today, one Santa Cruz restaurant had a leg of lamb, another had chicken, one had beef, and the remaining eateries were focusing their attention on appetizing fish and vegetable dinners.”

No substitutions were allowed, and margarine was served instead of butter when butter got really scarce. Milk by the glass was restricted; it was only to be cooked within the kitchen. Ordering coffee at a restaurant meant getting just one cup, with no seconds or top-offs, and only one teaspoon of sugar. The “help yourself” sugar bowls were completely taken off the table. Instead, your waitress would have the teaspoon ready on her tray or offered it in a tiny single-serving dish. Restaurant employees did their part rationing in local scrap drives by rinsing out and crushing tin cans and collected grease to then turn in to butchers. Due to a shortage of employees and the blackout periods at night, restaurants were open fewer hours.

There were also the non-essential travel laws for gas rationing which curtailed tourism. Local car dealers went from selling new cars to selling used cars and promoting car repair services. Tires were scarce due to rubber needed in the war effort. The consumer received an “A” card that allowed for just 3 gallons of gas a week. According to the “Occupational Driving Requirements” for regular deliveries of meat, produce, and eggs to restaurants and institutions, the truck companies had to fill out their own applications for receiving more gas coupons than the private citizens. They received a “T” sticker to post on the truck’s windshield. The local newspaper regularly warned about thieves and reported ration books were often stolen out of glove compartments.

Naturally, it helped that citizens were allowed to use cash to pay for their meals at restaurants, particularly if they ran out of coupons before the new ones were issued. During these frugal years, it helped a person’s morale to go out, even if for a simple cup of coffee and a piece of pie, to be with neighbors and friends. It was also very fortunate that the climate in Santa Cruz allowed for locally grown fruit and produce to be found almost all year long in their own backyards.