Pittsburgh loves to drink. In the early twentieth century, Pittsburgh, and western Pennsylvania, had been filled with breweries and distilleries. In fact, Pittsburgh alone had three major breweries: Fort Pitt, Duquesne, and the Independent Brewing Company. Smaller breweries dotted the landscape of Allegheny County. Even the Benedictine monks at St. Vincent Archabbey and Seminary made beer from the grains they grew on farmland. Drinking in Pittsburgh was a tradition. And prohibition didn’t do much to stop that.

Bootlegger Boom

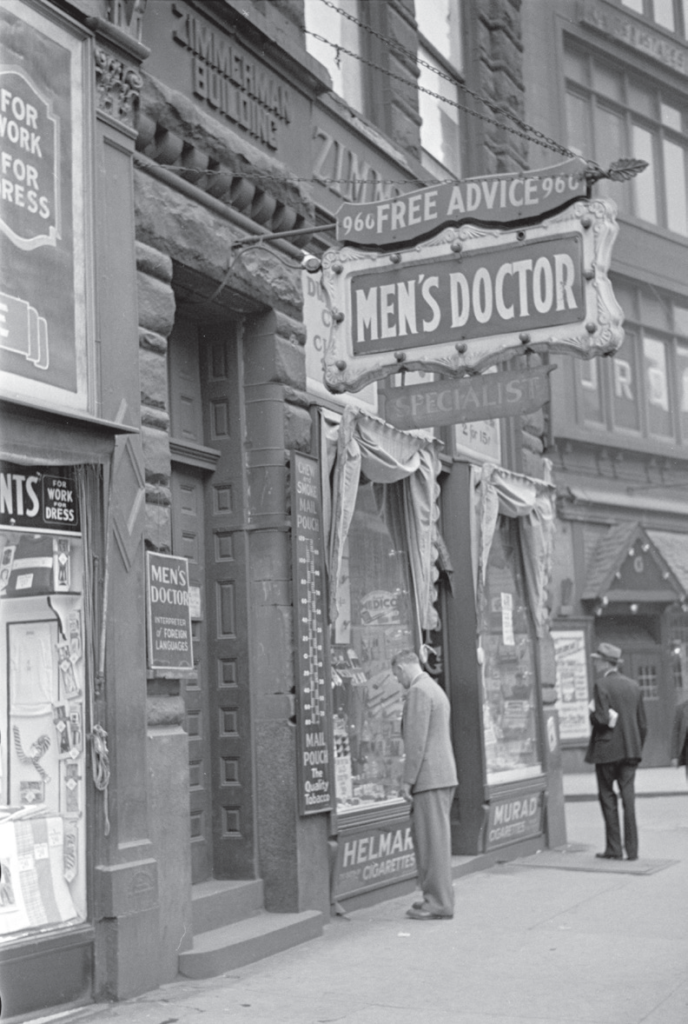

Once the National Prohibition Act, also known as the Volstead Act, was made the law of the land in 1919, the more than $1 billion worth of liquor stored in western Pennsylvania became illegal, and liquor dealers and saloonkeepers had to dispose of their stocks or face confiscation. Federal agents seized hundreds of gallons of alcohol just outside of Pittsburgh, and bootleggers became desperate to get pre-Prohibition liquor. Targets included warehouses and trucks, but bootleggers were desperate — even resorting to holding up trains, just like their 19th century frontier bandit counterparts had done. And more industrious bootleggers opened drugstores just so they could obtain medicinal whiskey. In Pittsburgh, there were nearly three hundred physicians granted special prescription pads to prescribe liquor to patients, and more than eleven thousand gallons were prescribed in the Pittsburgh region in 1930.

Cops versus Feds

Bootleggers weren’t boy scouts, and many employed violence. While dozens of speakeasies served booze to thirsty, normally-law-abiding Pittsburghers, the local police generally refused to crack down on speakeasies. The heavy lifting was left to federal agents, who had to get creative tracking down homemade whiskey. Some were were able to obtain “smell warrants” if they got a whiff of moonshine from a homemade still. One estimate counted ten thousand stills around Pittsburgh in 1926. Corruption wasn’t limited to local cops. Some federal agents accepted bribes to protect bootlegging operations or to tip off bootleggers to raids. Ultimately, there were separate systems of justice for bootleggers and the average citizen. A bootlegger could walk out of court with as little as a $100 fine.

“It’s almost impossible for a man to go into Pennsylvania to enforce the Prohibition law and come out clean…If he is not a crook when he goes in the chances are he’ll become one.” — Treasury Agent Saul Grill

RELATED: Vice in Prohibition Era Philadelphia READ NOW>

The Drinkingest Town in the West

All of Pittsburgh’s resistance to National Prohibition became the stuff of legend, and earned it the title “The drinkingest town in the west.” Politicians and bootleggers famously worked together to keep liquor flowing in Steel City. Actually, liquor smuggling in Pittsburgh was so well organized that local politicians used a shuttered brewery in eastern Pennsylvania to brew their own product. After Pittsburgh was divided into zones, saloons and speakeasies could purchase their supplies with ease.

Bootleg King

Pittsburgh businessman Martin Burke owned a restaurant, saloon, and hotel. In the early days of Prohibition, Burke made a fortune diverting medicinal liquor for his bootlegging operation, which stretched to Cleveland and Chicago. His reign ended abruptly in 1923, when he was shot as he answered his front door. Murders like Burke’s went unstopped through the decade and into the next as local police were powerless—or unwilling to address the source of the violence. Between 1926 and 1933, there were over two hundred gang murders in Pittsburgh.

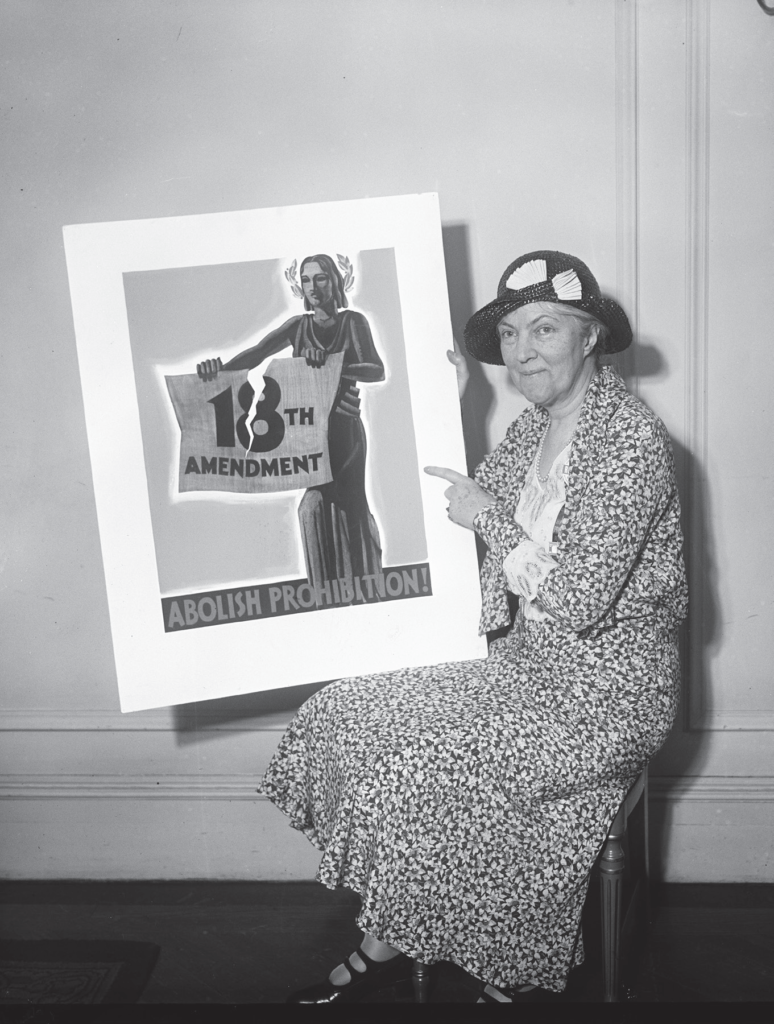

Repeal

Lawlessness and an overburdened court system took its toll on Pittsburgh. Political leaders, struggling to address problems from the Great Depression, looked to repeal the Great Experiment. Presidential candidate Franklin Roosevelt promised a Pittsburgh crowd he could ensure hundreds of millions of dollars of new revenue generated by a tax on beer once Prohibition was nixed. On December 5, 1933, the Twenty-First Amendment was ratified. Pittsburgh breweries reopened, and Pittsburghers rejoiced. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that defendants charged with violating the Volstead Act before repeal was enacted could not be prosecuted, thus freeing 250 defendants awaiting trial in Pittsburgh and Allegheny County. And now Pennsylvania was able to get in on the action with a two-dollar tax on each bottle of seized whiskey.

Learn More….

Bootlegging, bombs, murder, and more… all for the price of a drink. This is the history of Prohibition in Pittsburgh. When you work hard, you play hard, and Pittsburgh is a hardworking city. So, when Prohibition hit the Steel City, it created a level of violence and corruption residents had never witnessed. Illegal producers ran stills in kitchens, basements, bathroom tubs, warehouses and even abandoned distilleries.

War between gangs of bootleggers resulted in a number of murders and bombings that placed Pittsburgh on the same level as New York City and Chicago in criminal activity. Author Richard Gazarik details the shady side of the Steel City during a tumultuous era.