In 1860, the railroad wars that raged for decades reached a climax. Despite modest developments in infrastructure, America remained a largely untamed expanse of land —challenging to navigate regardless of transportation method.

The Civil War era promised to bring change; an economy perched on the precipice of domestic war often becomes malleable. Over the next 30 years, a handful of visionaries would vie to create a latticework of railways that would govern the flow of economic goods across America. Their combined efforts birthed the backbone of modern infrastructure.

In the fractured post-war society, the American railway continued to facilitate economic evolution, and literally unify a nation. This growth in transcontinental rail will forever be associated with a self-made man born and raised in New York City: Cornelius Vanderbilt.

The Capitalist Archetype Takes Shape

Cornelius Vanderbilt represented the first of his kind, a class of “entrepreneurial rock stars” with shared Machiavellian convictions. Vanderbilt functioned as the first domino in a shifting power dynamic, helping to christen the new socioeconomic hierarchy — one in which the businessman acts as the harbinger of revolution, not the politician.

Known as “The Commodore” for his no-nonsense entrepreneurial philosophy in fledgling steamboat ventures, Vanderbilt moved to the railroad industry after 50 lucrative years of maritime transportation.

As with all economic pioneers, Vanderbilt possessed a grand vision for some aspect of American industry. He imagined a continental infrastructure, a system untainted by government involvement — not designed by bureaucracy, but by him.

At the time, railroads represented the cheapest method for nationwide shipping; moreover, with domestic war looming, Vanderbilt shrewdly anticipated the importance of the railway system. In the late 1850s, he began to inch his way into the industry, serving first in an advisory capacity.

In 1863—two years into the Civil War—he acquired majority ownership of his first railway holding: The New York & Harlem Railroad (NY&H). Other acquisitions would soon follow.

By the end of the Civil War, Vanderbilt had carved a budding railway empire into the Northeastern countryside. The boy who launched his own ferry service at 16 had become the richest man in America.

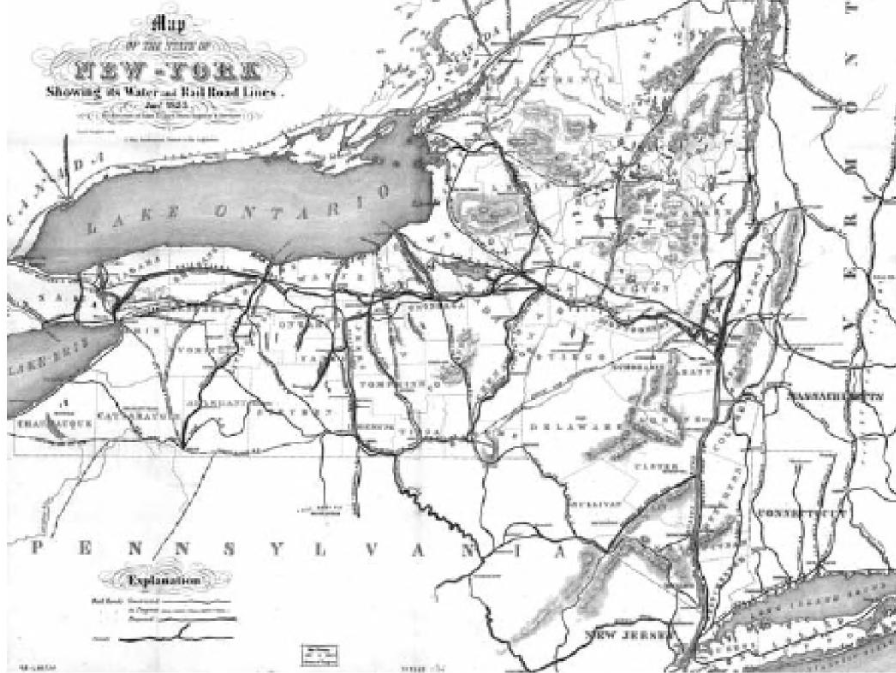

Still, the New York railroad wars persisted. After that first rather innocuous line between Albany and Schenectady in 1826 — which loyalists to the now obsolete Erie Canal waterway protested — Vanderbilt would finally enter the fray.

A Bottleneck at the Crossroads of Infrastructure

Many disparaged Vanderbilt’s first holding, NY&H Railroad, for its dearth of diverse routes. Up until the infamous “stock market corner” that precipitated Vanderbilt’s purchase of NY&H, only Vanderbilt adequately appreciated the rail line’s chief asset: The Albany Bridge. He ensured others would learn in time.

The Albany Bridge provided the only railway stretching across the Hudson River from New York City, serving as the sole rail access point to the largest port in America. Every other rail company assumed this checkpoint would remain permanently accessible to all domestic trade, but in this era of unregulated capitalism, Vanderbilt made his own rules.

After logisticians cemented America’s winter shipping schedule in 1866, Vanderbilt suddenly barred industry rivals from using the bridge. He famously stated, “We’re going to watch them bleed,” as his blockade began to strangle a vital revenue stream for many competitors. In the coming weeks, millions of pounds of cargo would stall in delivery.

Panic gradually seeped through the ranks of railway executives. Employees secretly scrambled to sell their increasingly devalued shares of company stock. When word reached Wall Street, a mass sell-off of railroad stock plummeted the prices of remaining shares.

As uncertainty spread, Vanderbilt relieved his competitors of their railroad stock at pennies on the dollar — and reopened the Albany Bridge.

Industry leader New York Central Railroad remained foremost amongst these purchases, a holding which Vanderbilt would merge in 1867 with the Hudson River Railroad and other minor acquisitions — all to form the largest consolidation of American railway in history.

Effects of a Laissez-Faire Marketplace

Vanderbilt’s marketplace behavior largely precipitated the creation of regulatory agencies that established antitrust law in the following decades.

For a moment, this era of free market capitalism allowed Vanderbilt and other industrial tycoons unprecedented influence on the evolution of American society. The absence of government regulations that now exist — which would have impeded Vanderbilt’s ability to consolidate railway holdings to an oligopolistic threshold — yielded two interesting effects.

First, the usual byproducts of a centralized industry surfaced, wherein prices and standards become controlled by a single corporation without the checks and balances provided by comparable competition.

The same laissez-faire marketplace also empowered Vanderbilt to grow America’s network of railroads with unfathomable speed. The burgeoning economy welcomed this injection of efficiency, and because Vanderbilt controlled a whopping 40% of the industry, his railway construction alone supplied 180,000 domestic jobs. Vanderbilt’s dreams for American transportation had blossomed before his eyes — at least temporarily.

Erie Line: The Ill-Sought Crowning Jewel of Vanderbilt’s Empire

Whether driven by a taste for power, the desire to shape America to his own blueprint or the loss of his favorite son and heir apparent during the Civil War — the entrepreneurial spirit burning within Vanderbilt started to consume him.

He began indulging his own legacy, cultivating an obsessive desire to make Erie Line the crowning jewel of his railroad empire. Eventually, this pursuit would pit Vanderbilt against a set of worthy adversaries.

With rail tracks connecting Chicago to New York, Erie Line operated the single most important global route. Its workforce also boasted a pair of shrewd up-and-comers, Jay Gould and Jim Fisk, two quirky thinkers with their own subtle Machiavellian streak. These men wanted “The Commodore” dethroned.

When Vanderbilt began purchasing shares of the Erie Line, Gould and Fisk concocted a loophole strategy using a previously obscured piece of fine print. Erie Line’s board of directors could issue new shares of stock unbeknownst to the public, legally diluting the value of every existing share. Vanderbilt purchased $7 million in watered-down stock from Gould and Fisk before becoming aware of his folly.

This public humiliation ignited a rivalry that lingered only with Gould, who openly smeared Vanderbilt’s reputation following the failed Erie acquisition. In the end, Vanderbilt would shift his attention from what he eventually labeled an “overbuilt American railway” to the freight traveling within: oil.

Whirlwind adventures of Jay Gould and Jim Fisk

Since the late 1850s, the Erie Line battled its own variation of financial strife. Jay Gould, Jim Fisk, and Daniel Drew orchestrated a myriad of stock manipulations during this period, now termed the Erie War. In the summer of 1868, Drew and Fisk would surrender control of the Erie Line to Gould, who ascended to its presidency.

Gould and Fisk became increasingly embroiled with Tammany Hall, an elite New York City political ring. “Boss Tweed,” the authority within Tammany Hall who shaped the 19th-century political sphere, would assume directorship of Erie Railroad in exchange for corrupt legislation.

In August of 1869, Gould and Fisk again found themselves scheming on behalf of Erie Railroad. They employed a simple strategy: begin acquiring gold to corner the market, which would simultaneously augment prices for both gold and wheat — and increase nationwide shipments that would ideally trickle through Erie Line.

On September 24th, 1869, the “Black Friday” gold panic descended on America as a culmination of Gould and Fisk’s endeavors, causing gold’s premium-over-face-value to dip 30%. This gold corner amassed Gould a tidy profit, cementing his public reputation as an economic wizard who could dictate the market on a whim.

Gould Ventures into the Rail Wars Alone

In 1873, Gould sought majority ownership of Erie Railroad by recruiting investments from foreign dignitaries and reputable American families. Chief amongst these prospective investors, a wealthy cousin in the famous Campbell family, possessed secretly sinister intentions.

When Gould attempted to bribe this Campbell with $1 million in stock, the man promptly cashed the stock and disappeared. Gould would later learn the true degree of his deception. The investor had no ties to the Campbell’s. He had been impersonating a variety of individuals for personal gain. His true identity surfaced as Lord Gordon-Gordon, a legendary British con man.

Gould immediately attempted to sue Gordon-Gordon, who fled to Canada after the justice system granted him bail. After pressing Canadian authorities to produce Gordon-Gordon to no avail, Gould and his associates took matters into their own hands. A ragtag group of American aristocracy, which included three future Congressmen and two Minnesota governors, attempted to kidnap Gordon-Gordon.

Ultimately, Canadian mounted police capture Gould and his colleagues, sparking an international incident between America and Canada. Thousands of Minnesotans volunteered for a military invasion of Canada. While the situation diffused in time, this incident eliminated Gould’s chances of ever controlling the Erie Railroad again.

Eventually, Gould would built up his own systems of railway, taking control of Union Pacific during the Panic of 1873, a massive financial crisis. Gould’s empire thrived on the shipments of local Midwestern and Western farmers in the coming decades.

Legacy of American Rail

Ultimately, the American railway became the catalyst for unprecedented economic growth in every industry. Yet it didn’t just cause the highest magnitude of economic growth, it spawned a whole new era of economic homeostasis — a modern, industrial, capitalist organism.

The railroad system provided the first major experiment in the infancy of capitalism’s industrial reorientation. Naturally, this infancy represents the most formative years — not necessarily in building concrete and lasting systems — but in building the collective capitalist mindset.

A new breed of leadership arose amidst the ashes of civil war, a class of rail barons that both set the standard and pushed the frontier of “the American dream.”

Final thoughts

What drove these pioneers? What defines them? Unwavering determination undoubtedly unites these individuals, but what lies at the heart of their successes?

Jacob Bronowski, in his documentary series Ascent of Man, asserts, “What we call cultural evolution is actually the expansion of human imagination.”

Perhaps this best defines the pioneers of an entrepreneurial age that has persisted since Vanderbilt: an imagination that is prone to uncommon, bold dreams, dreams for both themselves and the future of America.