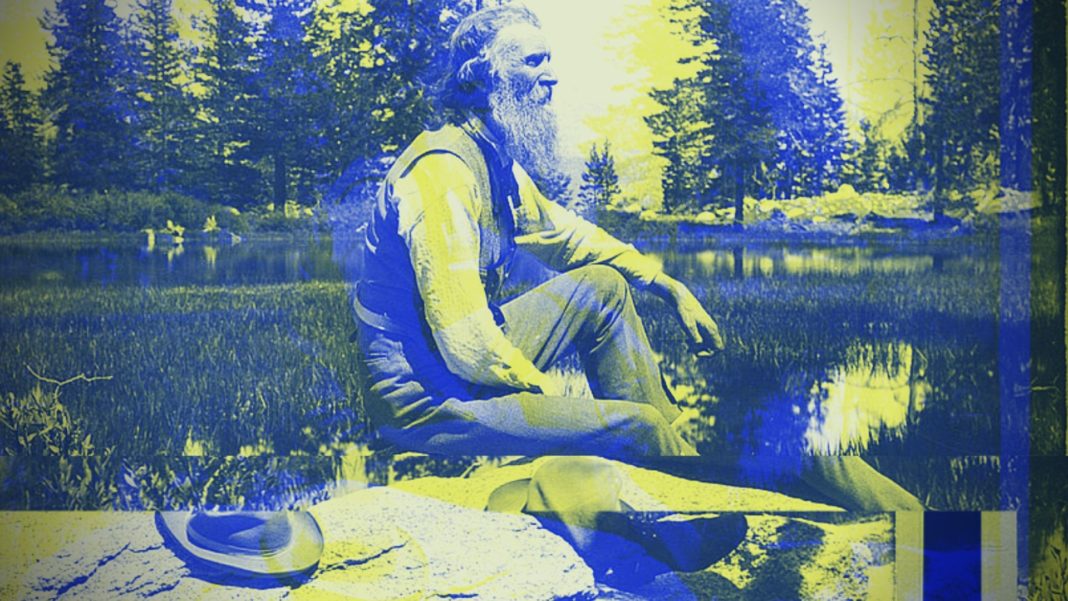

The following is an excerpted chapter from High Vistas: An Anthology of Nature Writing from Western North Carolina & the Great Smoky Mountains, recounting John Muir’s 1867 walk from the mountains of western North Carolina to the gulf.

Some of America’s finest explorers and naturalists have made their way into the mountains of Western North Carolina. These number botanists such as William Bartram, André Michaux, John Fraser, John Lyon, Asa Gray and Charles Sprague Sargent; geologists Arnold Guyot and Arthur Keith; ornithologist William Brewster; and twentieth-century writers such as Horace Kephart, Donald Culross Peattie, Roger Tory Peterson and Edwin Way Teale. But none of these—with the possible exceptions of Bartram and Peterson—can rival John Muir’s name recognition. As the founder and first president of the Sierra Club, he was without doubt this country’s most influential conservationist. Muir (1838–1914) was born in Dunbar, Scotland, the son of Daniel Muir, a farmer. The family migrated to a homestead near Portage, Wisconsin, in the late 1840s. Muir Sr. is reputed to have been a harsh disciplinarian who worked his family from dawn to dusk. But in his free time, his son became a keen observer of the natural world.

RELATED: Celebrating the History of the Greensboro Sit-ins through Pictures

In 1860, Muir entered the University of Wisconsin, where he made excellent grades; nevertheless, after three years, he left Madison to travel through the Northern United States and Canada, thereby increasing his knowledge of the natural world, especially of plants. Then, in 1867, while working at a carriage parts shop, he suffered a blinding eye injury that changed the course of his life. After miraculously regaining his sight, the rejuvenated young man resolved to turn his attention fulltime to the “University of the Wilderness.”

Already an accomplished long-distance walker, on September 1, 1867, Muir initiated years of wanderlust with a little stroll from Indianapolis, Indiana, where he was then residing, to Cedar Key, Florida. Traveling light, he carried a small bag that contained a comb, brush, towel, soap, a change of underclothing, a copy of Robert Burns’s poems, Milton’s Paradise Lost, a copy of the New Testament and a notebook, in which he made daily observations and rough pencil sketches of plants and animals. Written on the inside cover of the notebook are the words: “John Muir, Earth-planet, Universe”—his address for the remainder of his life.

The following year, Muir went to California, heading directly from San Francisco to the Sierra Nevada, on foot. He fell in love with the Sierras and was entranced by Yosemite Valley. Accordingly, he campaigned for the establishment of Yosemite National Park, which became a reality in 1890, and two years later he organized the Sierra Club to foster conservation of wild lands. Muir served as the club’s president until his death. During the years 1896 and1897, his influence with President Grover Cleveland helped establish thirteen forest reserves—which evolved into today’s national forests. Along with President Theodore Roosevelt, who became a close friend after camping with him in Yosemite in 1903, Muir fostered the designation of additional national forests, national monuments such as Muir Woods and national parks such as Sequoia.

RELATED: Building an Empire: Restoring the Biltmore Estate

His first book, The Mountains of California, was published in 1894. It was followed in his lifetime by others such as Our National Parks (1901), Stickeen (1909), My First Summer in the Sierra (1911) and The Yosemite (1912). Travels in Alaska (1915), The Cruise of the Corwin (1917) and Steep Trails (1918) appeared posthumously. The nature notebook Muir kept during his 1867 walk, ably edited and with an important introduction by William Frederic Bade, was published by Houghton Mifflin Company in 1916 as A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf. Bade titled the second chapter of the book “The Cumberland Mountains.” Therein, one finds Muir’s all too brief account of his crossing of the far southwestern tip of North Carolina. “Mr. Beale”—the sheriff Muir encountered in Cherokee County—was William Beale.

Margaret Walker Freel, in Our Heritage: The People of Cherokee County, North Carolina, 1540–1955 (1956), described him as a native of Yorkshire, England, who had attended Oxford University before moving with his family to Murphy in 1855. He served as Cherokee County’s sheriff during the Civil War and for some time afterward, even though “there was feeling that he was in sympathy with the North, and at times he had to go to the mountains for safety.” He was also a schoolteacher, storekeeper, mineralogist and surveyor, “who had the first transit ever brought to the county,” as well as “the first wagon with manufactured wheels and the first lamp which burned kerosene oil.” Such was the background of the local man who befriended John Muir in September 1867, during his long walk from Indianapolis to Cedar Key.

John Muir’s Thousand-Mile Journey

September 18. Up the mountain on the state line. The scenery is far grander than any I ever before beheld. The view extends from the Cumberland Mountains on the north far into Georgia and North Carolina to the south, an area of about five thousand square miles. Such an ocean of wooded, waving, swelling mountain beauty and grandeur is not to be described. Countless forest-clad hills, side by side in rows and groups, seemed to be enjoying the rich sunshine and remaining motionless only because they were so eagerly absorbing it. All were united by curves and slopes of inimitable softness and beauty. Oh, these forest gardens of our Father! What perfection, what divinity, in their architecture! What simplicity and mysterious complexity of detail! Who shall read the teaching of these sylvan pages, the glad brotherhood of rills that sing in the valleys, and all the happy creatures that dwell in them under the tender keeping of a Father’s care?

RELATED: Theodore Roosevelt’s Epic California Camping Trip

September 19. Received another solemn warning of dangers on my way through the mountains. Was told by my worthy entertainer of a wondrous gap in the mountains which he advised me to see. “It is called Track Gap [now Track Rock Gap State Archaeological Area in north Georgia],” said he, “from the great number of tracks in the rocks—bird tracks, bar tracks, hoss tracks, men tracks, all in the solid rock as if it had been mud.” Bidding farewell to my worthy mountaineer and all his comfortable wonders, I pursued my way to the South.

As I was leaving, he repeated the warnings of danger ahead, saying that there were agood many people living like wild beasts on whatever they could steal, and that murders were sometimes committed for four or five dollars, and even less. While stopping with him I noticed that a man came regularly after dark to the house for his supper. He was armed with a gun, a pistol, and a long knife. My host told me that this man was at feud with one of his neighbors, and that they were prepared to shoot one another at sight. That neither of them could do anyregular work or sleep in the same place two nights in succession. That they visited houses only for food, and as soon as the one that I saw had got his supper he went out and slept in the woods, without of course making a fire. His enemy did the same.

My entertainer told me that he was trying to make peace between these two men, because they both were good men, and if they would agree to stop their quarrel, they could then both go to work. Most of the food in this house was coffee without sugar, corn bread, and sometimes bacon. But the coffee was the greatest luxury which these people knew. The only way of obtaining it was by selling skins, or, in particular, “sang,” that is ginseng, which found a market in far-off China.

My path all to-day led me along the leafy banks of the Hiwassee, a most impressive mountain river. Its channel is very rough, as it crosses the edges of upturned rock strata, some of them standing at right angles, or glancing off obliquely to right and left. Thus a multitude of short, resounding cataracts are produced, and the river is restrained from the headlong speed due to its volume and the inclination of its bed.

All the larger streams of uncultivated countries are mysteriously charming and beautiful, whether flowing in mountains or through swamps and plains. Their channels are interestingly sculptured, far more so than the grandest architectural works of man. The finest of the forests are usually found along their banks, and in the multitude of falls and rapids the wilderness finds a voice. Such a river is the Hiwassee, with its surface broken to a thousand sparkling gems, and its forest walls vine-draped and flowery as Eden. And how fine the songs it sings!

In Murphy I was hailed by the sheriff who could not determine by my colors and rigging to what country or craft I belonged. Since the war, every other stranger in these lonely parts is supposed to be a criminal, and all are objects of curiosity or apprehensive concern. After a few minutes’ conversation with this chief man of Murphy I was pronounced harmless, and invited to his house, where for the first time since leaving home I found a house decked with flowers and vines, clean within and without, and stamped with the comforts of culture and refinement in all its arrangements. Striking contrast to the uncouth transitionist establishments from the wigwams of savages to the clumsy but clean log castle of the thrifty pioneer.

September 20. All day among the groves and gorges of Murphy with Mr. Beale. Was shown the site of Camp Butler where General Scott had his headquarters when he removed the Cherokee Indians [in 1838] to a new home in the West. Found a number of rare and strange plants on the rocky banks of the river Hiwassee. In the afternoon, from the summit of a commanding ridge, I obtained a magnificent view of blue, softly curved mountain scenery. Among the trees I saw Ilex [holly] for the first time.

High Vistas: An Anthology of Nature Writing from Western North Carolina & the Great Smoky Mountains,

By George Ellison

“High Vistas” is the first anthology devoted to nature writings on Western North Carolina and the Great Smoky Mountains. Each selection features a biographical essay introducing each author from celebrated naturalists John Muir and William Bartram to lesser-known writers whose words deserve to be heard and reveals how he or she went about exploring and depicting the region. Searching for rare wildflowers and elusive birds, scaling vertical cliffs, experimenting with medicinal plants, exploring a vast cavern, enduring horrific thunderstorms and encountering timber wolves, panthers, black bears and giant rattlesnakes are just some of the adventures that unfold in these pages.