At 12:15 AM on April 15, 1912, a message rang out across the Atlantic: “CQD MGY 41.46 N 50.24 W.” The message, sent by a Marconi radio operator, came from the doomed RMS Titanic 30 minutes after striking the iceberg that would end the ship’s maiden voyage. It was followed by a series of messages from the ill-fated vessel, many of which went unreceived, or failed to establish any meaningful contact. Meanwhile, novice radio operators on land clogged the airwaves with false news of the sinking, leading to the early spread of misinformation, and later, overwhelming public ire. While the Titanic’s radio and its operators were to thank for the 745 survivors of the tragedy, the malicious behavior of amateur operators was blamed in the disaster’s aftermath – raising questions of how something so disastrous had been allowed to occur, and what could have been done to avoid it altogether.

Radio technology was still in its infancy in 1912, and was surprisingly complicated to use: Restricted to Morse code for transmissions, most radio transmitters at the time were referred to as “spark” transmitters, as they relied on sparks of electrical energy. This type of transmitter could not continuously emit radio signals, making voice messages virtually impossible. Spark communications also covered a large bandwidth, making interference from outside messages inevitable. As a result, despite being marketed as a maritime technology, radio was considered a relatively inefficient means of emergency communication.

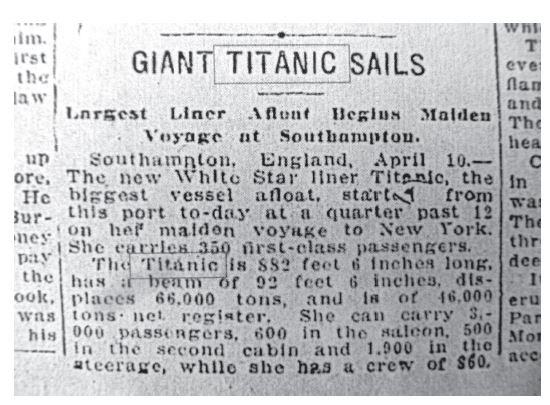

This inefficiency was evidenced by its problems on the Titanic – although a radio was onboard the ship with two operators, it was never intended for emergency communication. Instead, the “Marconi room” was primarily for passengers to send telegrams from the ship as it journeyed from Southampton to New York City. The Titanic was one of only four ocean liners to employ two Marconi company radio operators, named Jack Phillips and Harold Bride. Both Phillips and Bride struggled with the volume of telegram requests, which were difficult to transmit to the far-off Marconi station in Newfoundland.

This focus on telegrams led to the first of many mistakes by the Marconi operators, as they ignored several warnings of ice, failing to deliver them to the bridge for review. Their negligence was complicated further by the fierce competitive nature of their position’s – in 1912, Marconi nearly held a monopoly over the radio industry, and there was an intense rivalry with their main competitor Telefunken. As a result, even after the Titanic had begun issuing distress signals, some Telefunken operators who answered were told to “keep out” by Phillips, who refused to deal with his company’s competition. As a result, while the radio could have helped to prevent the tragedy outright, it instead only helped to save a small portion of those onboard the ship.

The limited scope of early radio technology was further complicated by its popularity with novice operators, who neglected to keep airwaves clear for official messages, and often maliciously interfered with transmissions. Professional radio operators had struggled for years with amateur operators (derisively called “hams” for their “ham-fisted,” poor Morse code skills) interfering with messages. Many of these amateur operators were younger than twenty years of age, and considered it good fun to play practical jokes on the Navy by delivering false messages. They also tended to clog the large bandwidth of spark transmitters, making it difficult for others to send crucial messages.

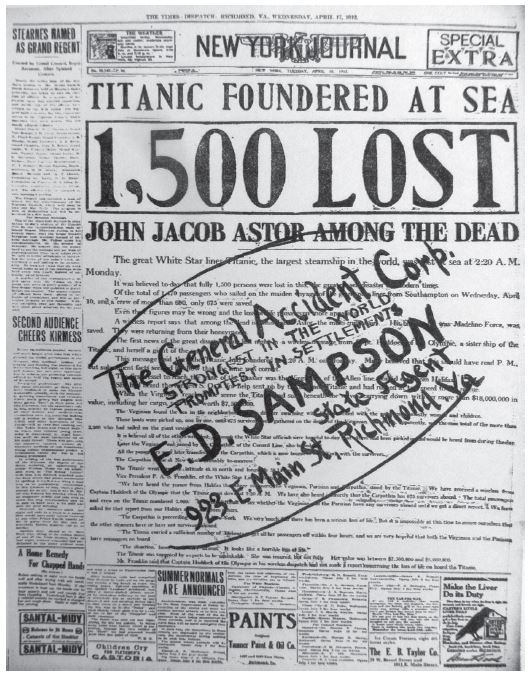

The government failed to remedy the complaints made about amateur operators, who were completely unregulated at the time of the Titanic’s sinking in 1912. This led to several complications concerning the disaster, particularly with information relayed in the aftermath. It had been initially reported on land that a radio transmission claiming that “all Titanic passengers safe; towing to Halifax” had been delivered to a Marconi station, which was quickly printed within major newspapers to assuage the fears of passengers’ relatives. The falsity of this transmission was quickly discovered, as the truth began to spread late on the 15th, nearly a day after the crash. Many were incensed at such misinformation, and blame quickly fell onto ham operators. It was suggested by Captain Herbert Haddock of the Titanic’s sister ship RMS Olympic that novice radio operators had interfered by stitching together two separate telegrams (one asking “are all Titanic passenger safe,” and another stating “towing oil tank to Halifax”) to create the misleading message.

The accusations directed at amateur radio practitioners did not stop there: It was also claimed that ham operators had been “gumming up” the available bandwidth, making it difficult for the Titanic to send messages, or be heard by nearby ships. In the weeks following the Titanic’s sinking, both the UK and US launched investigations into the catastrophe, concluding that several factors had contributed to the large-scale of the disaster, including failures in radio and “amateur interference,” as Marconi officials blamed “unrecognized stations” making communication difficult. As a result, a grand majority of the blame of the sinking was placed on faulty radio operation, particularly by amateur users, along with a lack of sufficient lifeboats and poor leadership from the vessel’s captain.

The Titanic sinking had some inevitably large effects on radio and broadcasting, given all of the confusion and fury over the sinking. Only four months after RMS Titanic was lost, the American government passed the Radio Act of 1912 – the law was the first action taken by the US government to gain control of the airwaves, and required all operators to hold a valid federal license to use radio equipment. In addition, it restricted amateur users to bands less than 200 meters – wavelengths far below where official maritime communications would be conducted, reducing the chances of interference with transmissions. These requirements carried hefty consequences if ignored: Someone found in violation could be subjected to a fine of up to $2500 USD (approximately $63,000 USD today) and up to five years in prison.

Amateur radio soon found itself with far less operators, forever changed by the events onboard the Titanic, though it was impossible to blame only one factor in the sinking. Unfortunately, the combination of poor leadership, a lack of emergency preparedness, and both professional and novice radio errors was simply too much for the Titanic to bear – creating one of the greatest maritime disasters in history, and leaving an indelible legacy on those industries surrounding it.

For more information on RMS Titanic, check out Richmond, Virginia, and the Titanic to learn about the ship’s connection with the people of Virginia. Or try our radio titles for more information on broadcasting in the United States.