This article was adapted from Evansville in World War II By James Lachlan MacLeod (The History Press)

Before the start of World War II, Evansville, Indiana, was a relatively sleepy Ohio River city, badly hurt by the Great Depression and with only a couple companies working on military contracts.

And yet, by the end of the war, the city had been transformed into a uniquely productive center of manufacturing. Tens of thousands of new workers flooded into Evansville, to work at Republic Aviation or the Evansville Shipyard. The landing ship tank or “LST” that was built at the shipyard made an especially large impact—not just on the Evansville economy but on the fate of the war itself.

Citizen Resilience

In the early months of 1941, Evansville’s most prominent companies and citizens were worried the coming war would hurt their modest Midwestern city. As a member of the chamber of commerce admitted, “It looks like Evansville is the forgotten country, or no-man’s land. . . . We do not seem to be able to interest any one in Washington in this part of the state.” But those companies and citizens didn’t give up. They formed the Manufacturers Association Defense Committee, which conducted “a survey of all available machine and personnel facilities within 50 miles of Evansville to make it possible to pool resources.” Thanks to their hard work, the federal government didn’t forget Evansville—it decided to construct new facilities there.

Public Library (EVPL via Evansville in World War II By James Lachlan MacLeod (The History Press, 2015 $21.99)

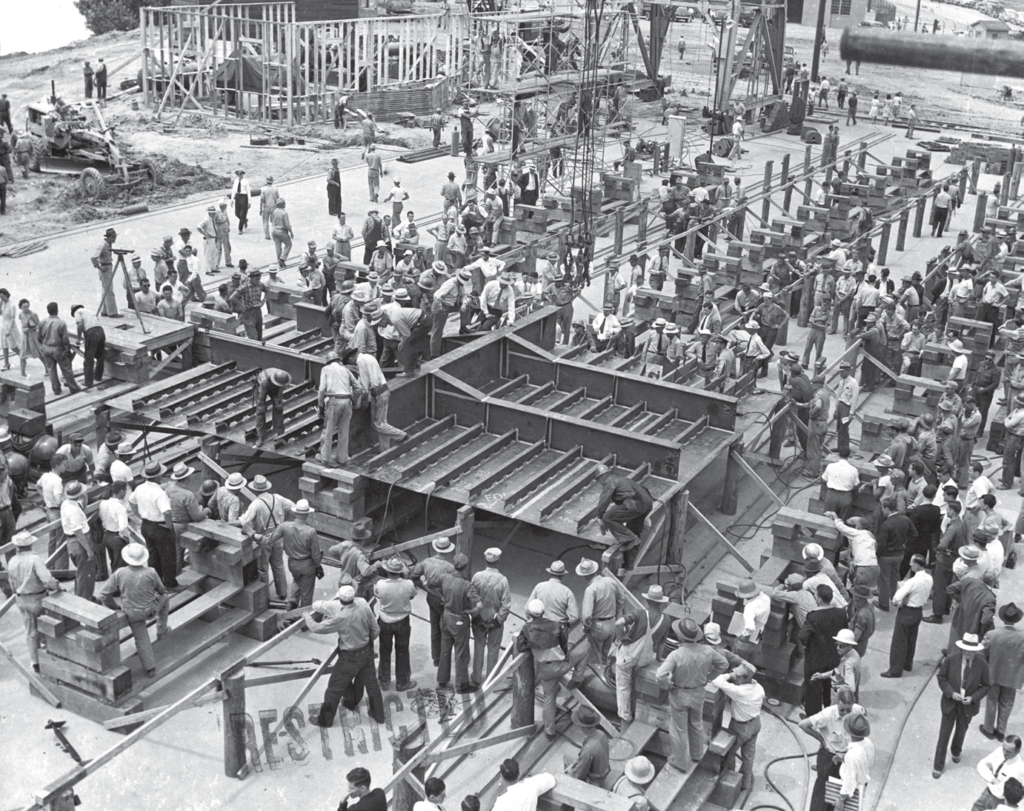

On February 14, 1942, the Evansville Courier revealed that a shipyard was coming and that it was to be located on some forty-five acres of mostly derelict land along the Ohio River between the Mead Johnson Terminal and the Southern Indiana Gas and Electric Company Power Station. Hundreds of people started showing up to pick up applications. The navy kept a close eye on the construction. Commander F.M. McWhirter, the navy’s district security officer, wrote to the yard’s manager: “The danger of espionage and sabotage to all facilities producing war material is ever-present. Your shipyard is vital to the success of the whole war effort.”

Enemies Among Them?

Worries over espionage and sabotage nearly shut down one of Evansville’s most beloved landmarks—Reitz Hill, which still dominates the West Side of Evansville and offers a commanding and spectacular view of the downtown and the Ohio River. The navy considered closing Reitz Hill to all traffic because it looked down on the new shipyard, and the navy’s lawyer argued that closing it was essential for “protection against sabotage and espionage.” The authorities felt that they had to go further and completely close Lemcke Avenue for fear of photographs being taken from a moving vehicle.

Reitz Hill was a popular spot for local couples, and the Evansville Press’s “Home Front” column thought that the measure was excessive, joking that the navy was “afraid of peekers not petters.” Eventually the authorities decided that closing the street was not essential, and Lemcke, along with Reitz Hill, remained open for the duration of the war, although it was kept under surveillance by shipyard security guards using telescopes.

Once that shipyard was operational, it specialized in building LSTs. An LST was designed to sail right up onto a beach and then open its huge bow doors to disembark its cargo of tanks and other vehicles directly onto the beach. The Evansville Shipyard made more than 150 LSTs. With a peak employment of just under 20,000 workers, it became the largest inland facility that manufactured LSTs in the world.

“the destinies of two great empires . . . seem to be tied up in some God-damned things called LSTs.”

– Winston Churchill

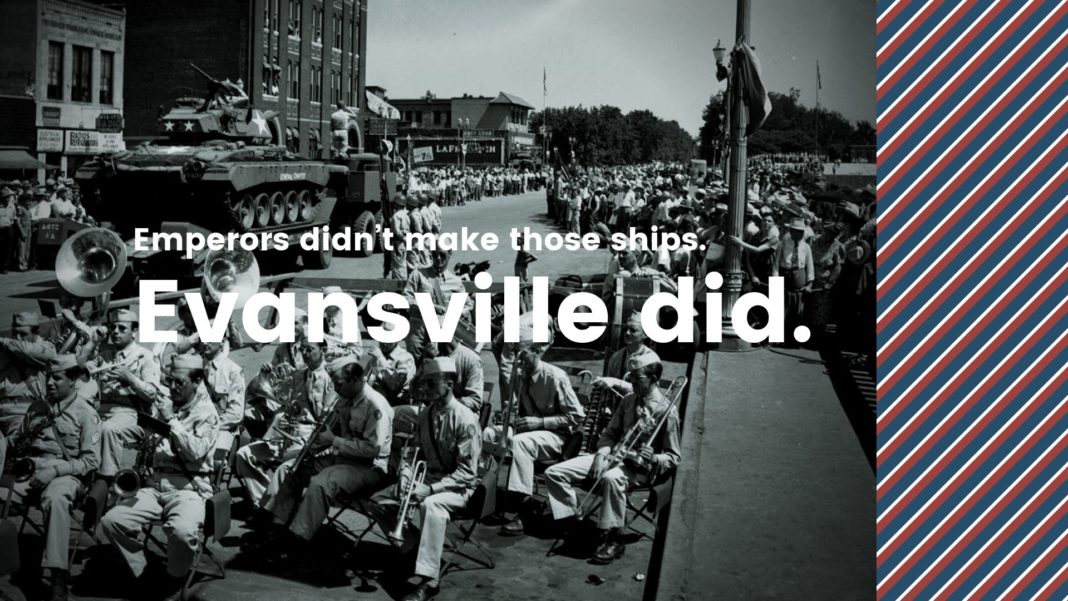

The LSTs were a crucial piece of technology during the war—not glamorous, but important, reliable, and easy to overlook, just like the city that made them. No less an authority than British prime minister Winston Churchill remarked that “the destinies of two great empires . . . seem to be tied up in some God-damned things called LSTs.”

But emperors didn’t make those ships. Evansville did.