While most Americans associate Daniel Boone with Kentucky, the famous frontiersman passed some important years in Missouri as well. Here, in an exclusive excerpt from his new book Finding Daniel Boone, Ted Franklin Belue provides a fun and detailed tour of the Daniel Boone Home near Defiance, Missouri.

***

Walking on Boone turf elicited an array of feelings as I trudged up the rise to the home where Daniel “passed off gently.” William Ray intercepted me. We shook hands but we’d met once before, he said, at a Bluegrass Alliance and New Grass Revival bluegrass jam at Rudyard Kipling’s, a pub located at “Mile 604 on the Ohio River.”

I went blank. “What’s ‘Mile 604’?”

He smiled, brown eyes crinkling behind his wire-framed glasses.

“Louisville. Starting up at Pittsburgh at Mile 0. The river is 981 miles long.”

Bill—tall, lanky, dark-haired under his dirty green Boone Home cap—is a true “Kaintuck,” as Frenchmen called boatmen. For six years he plowed the Ohio as a deckhand or manned the Belle of Louisville—“I’ve been as far down as Henderson and as far north as thirty miles past Marietta.” Like most riverboat men he’s a free-spirited, engaging fellow. He trains guides, researches and plans events. He’s an old-time fiddler and plays banjo, talents that go well here or on the Ohio. We made plans to pick some Boone-era tunes after hours.

A long rock wall bordered our left. Remnants of a well and Nathan’s once-gurgling spring—these days barely a trickle—were to our right, once considered the property’s rear. “We’ve found evidence of cabins right about here.” He pointed a few yards away. “Maybe three, close in proximity. It makes sense that their cabins would have been close to the source of water.”

One structure may have been slave quarters.

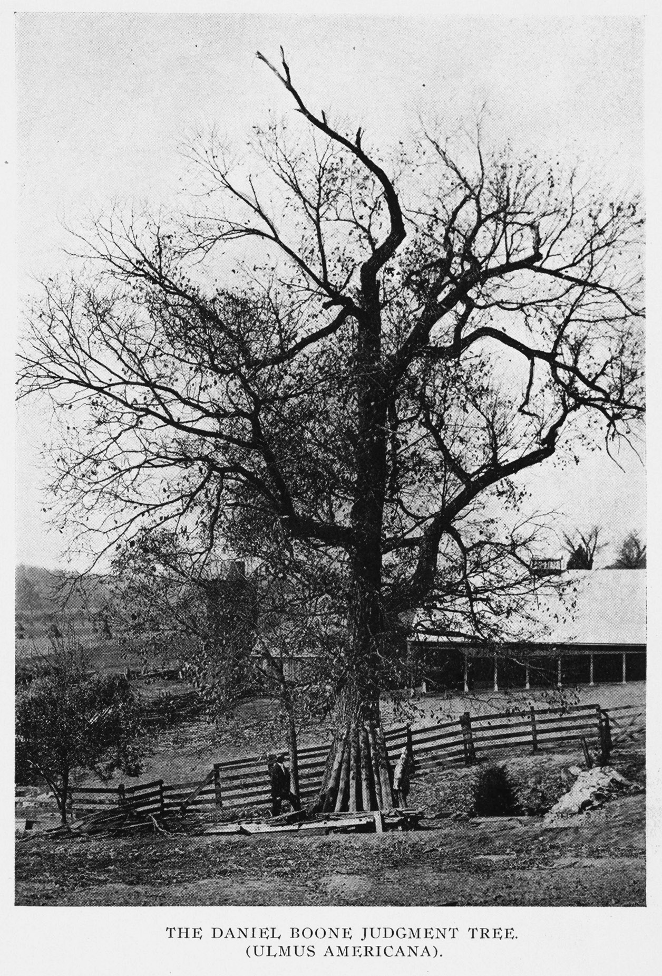

Nearby lay the gray masonry core of a giant American elm (Ulmus americana), Daniel’s so-called Judgment Tree, looking like a derelict Cecil B. DeMille movie set prop, circa 1935. Here, legend has it, Boone—of stout build and ruddy faced, with white hair queued and attired in earth-toned homespun or a linen ruffled shirt, buckskin coat and weskit or wearing a woolen regimental pulled over a walnut-dyed shirt and breeches—prevailed over his shade-tree court.

It’s a romantic image, an untutored woodsman acting as magistrate under a splattering of sunlight filtering through shimmering, saw-toothed foliage. Such “council elms” soared 150 feet or more. At thirty feet the trunk splits, forks leafing skyward above billowing, dappled shadows. In 1775, beneath Boonesborough’s Divine Elm, Boone and other assembly delegates doffed their hats as an Anglican minister preached the gospel in the Bluegrass.

As “Commandant of the District of the femme osage,” he sentenced lawbreakers, signed documents and brokered peace between brawlers like James Meek who “bit off a piece of Bery Vincent’s Left Ear,” governing “more by equity than by law.” Spain’s lieutenant governor Carlos Delassus, who handed rule to Americans, called him “a respectable old man, just and impartial” and advised that “in view of my confidence in him for the public good,” he should stay at his post. “Whipped and cleared” was a usual sentence or fines paid in cash, livestock or labor.

One hothead displeased at his verdict vowed he’d fight him if he were not so old. Boone threw down: “Let not my gray hairs stand in your way. I am old enough to whip the likes of you.” Swift justice kept men out of jail to provide for families. His was an equitable system.

In 1925 when Francis Marion Curlee bought the home the Judgement elm was showing the ravages of two hundred years. Curlee excised its dead wood, fertilized and concreted its decaying trunk and limbs—standard remedy for languishing hardwoods. Like a “dentist when cleaning a tooth for filling. If all the decay is not removed, it will continue as if the filling had not been placed.”

Photos prior to Curlee’s era show the elm leafed out. G.H. Pring, horticulturist for Missouri Botanical Gardens, stands by the trunk, its girth making five of him. He estimated it at “sixty-five feet high, forked about three feet from the ground, each branch measuring nine feet in circumference at the fork. The main trunk is sixteen feet six inches in circumference two feet from the ground.”

Related: The Rice Family and Napa’s Hidden History of Resistance

When the defoliated crown crashed to earth, workers jammed rebar down its erect trunk and pumped in more concrete. As its pith rotted around the concrete and the scaly bark peeled away (to be scooped up by tourists), it left a duplicate stone elm sprouting steel spikes. Dan’s ominously leaning Judgment Tree was roped off to keep it from toppling over on someone.

“I’ve seen a photo of it standing in the 1970s,” Bill Ray said. “It was stripped. No green, no bark. With the rebar it looked pretty foreboding—like something out of a Tim Burton film.” He sighed. “One of the misconceptions we get from people is this was ‘Boone’s Hanging Tree.’”

Actually, there were two Judgment Trees. Nathan’s elm was the second. How often Boone held court here is speculative, though it was less than on his land near Matson where he lived and presided until 1805. By the time he moved here this was U.S. territory evolving to statehood. As Governor William Henry Harrison of the Louisiana Territory was appointing district judges, any Boone-arbitrated decisions would have dubious legal standing.

“This is one of the more exciting finds we’ve had.” Bill pointed to an archaeological test pit exposing a tight vertically laid stone phalanx. “We found this cobblestone path. Theoretically, you could be looking as early as 1810, but it’s more probable you’re looking at the 1820s or so.”

Maybe by this route (or the river) Nathan got word of their father’s death to his brother Jesse, serving in St. Louis’s legislature. The fourthborn son survived Boonesborough’s siege, inspected salt-works in Virginia and Greenup County and was a Kentucky judge. He married Chloe Van Bibber and came here after his parents did. To honor Dan’s memory, Missouri’s Constitutional Convention adjourned for twenty days, yet Jesse missed his pa’s funeral. Maybe he wasn’t well, as consumption killed him by year’s end, leaving Chloe with five sons and four daughters. Chloe died the following year.

St. Louis’s Missouri Gazette published her father-in-law’s obituary. Riddled with errors, it still captures the spirit of the man beneath the buckskin—its length confirming Boone’s stature:

Death of Col. Daniel Boone

Died—At Charette village, in the state of Missouri, on the 26th September last, Col. Daniel Boone, the first settler of Kentucky, in the 90th year of his age. He was a native of Buck’s County, Pennsylvania; he left that state at 18 years old, and settled in North Carolina. He was one of the few men of our country whose enterprise led him to search into the wilderness for the best tracts of land for man to inhabit. As early as the year 1775, he removed with his family, and settled on the Kentucky river, (with the loss of his eldest son, killed by the Indians,) at a plain now called Boonesborough, then an Indian country, where he remained until the year 1799. During this period of time, although most of his life had been spent in agricultural pursuits, and he had been frequently honored by his countrymen, as a member of the Virginia Legislature, and lived, at the close of the Revolutionary war, in peace and plenty, yet, such was his delight in hunting—such his devotedness to it, that, in the year 1799, with a numerous train of followers, he removed from Kentucky, and settled on the Femme Osage River, which empties itself into the Missouri River, about 50 miles above its mouth, then a wilderness. The year after he discovered the Boon’s Lick country, which now forms one of the best settlements of the state. In that year he also visited the head waters of the Grand Osage river, and spent the winter upon the waters of the river Arkansas. At the age of 80, in company with one white man and a black man, whom he laid under strict injunction to return him to his family, dead or alive, he made a hunting trip to the head waters of the Great Osage, where he was successful in trapping beaver, and in taking of other game.

Colonel Boone was a man of common stature, of great enterprise, strong intellect, amiable disposition and inviolable integrity—he died universally regretted by all who knew him; and such is the veneration for his name and character, that both Houses of the General Assembly of this state, upon information of his death being communicated, resolved, to wear crape on the left-arm for 20 days, in token of regard and respect for his memory.

Bill Ray and I stayed on the walkway up to Nathan and Olive’s front door; in their day it was their home’s backdoor. The home fronted the creek six hundred yards southward and was bordered on the northern shore by Boone’s Trace, Daniel’s wagon route circumambulating the Femme Osage.

I stooped to peer into a slot by the door frame; the slots were blocked off on the interior end. I shoved my fist in, stopping three inches past my wrist. Using the door as a center point to divide the home’s face, between it and four window frames were three slots per side, each five and a half inches across by eight and a half inches high and fifty-five inches from the ground. Home lore deems these as “gun ports” or “loops”—fashioned so that Nathan and kin could poke guns out to blast away. Perhaps this tale was birthed by Curlee, whose construction crew, while “working on the walls of the house… found at the front six stones practically identical in size, evenly spaced and at the same height from the floor. Curiosity prompted investigation, and it was found that they filled what appeared to have been portholes. The conclusion that these openings were designed for portholes is natural, for at the time the house was built, it was surrounded by a wilderness through which Indians lurked and wandered.”

To me (I’m five foot eight, same as Dan), these ports seemed a mite low to shoot out of unless the home’s defenders were hobbits. Gun ports typically flare at the sides for aiming and side-to-side mobility; these were rectangular, sharply edged and compact. And why ports just to the northeast?

I nodded to my kind host who I suspected didn’t buy the story either.

Others say the holes held scaffolding—an explanation less thrilling than whooping, war-painted apparitions circling on dashing ponies shrouded from flintlocks blazing away. Such skirmishing happened up the road a few miles at Jonathan Bryan’s. Not here.

On entering, the first door on the right opens to narrow stairs—thirteen steps, not counting the landing—leading down to the basement. A grandfather clock occupied a hall corner by Karl Bodmer and Jean-François Millet’s lithograph, The Capture of the Daughters of D. Boone and Callaway by the Indians. Above the mantle in the parlor—the wide, open-air sitting room leftwards where the Boones greeted visitors—was a finely done oil-on-canvas bust of Daniel reminiscent of John James Audubon’s Boone.

The darkened timbers above the smoke-stained hearth told of many fires. Between the two windows on the north-south walls hung portraits of Francis and Ursula Curlee across from the first official presidential lithograph, The Courtship of Washington, suspended above an old chair and couch. The parlor was light federal blue and trimmed in walnut. Its patinaed floors were hammered with square-headed nails and the room smelled of age and smoke.

“We can head into the death room,” Bill said.

***

Want to read more? Check out Finding Daniel Boone: His Last Days in Missouri and The Strange Fate of His Remains and other similar titles at arcadiapublishing.com!