In 1876, years before South Dakota would become a state, The Yankton Press and Dakotian reported that “A large party will leave Yankton for the Black Hills. A party from Wisconsin will also leave today and join the Yankton party. The train will consist of some ten or fifteen wagons. The party is well-outfitted and well-armed.” But the train in question wasn’t powered by steam, and it didn’t follow tracks. That technology had not yet reached this part of the future state. Instead, this “train” was a long line of wagons pulled by oxen, one of thousands of bull trains that would haul miners, settlers and ne’er-do-wells needed to survive in that isolated prairie oasis.

In April 1877, the newspaper reported, “The Dakota Central [Railroad] brought three coaches containing two hundred Black Hillers.” Two days later, the same newspaper reported, “About four hundred men arrived on last night’s train from Sioux City, mostly [bound] for the Black Hills.” In its March 5 edition, the newspaper reported, “Thirty men from Dubuque [Iowa] will arrive this week en route to the Black Hills.”

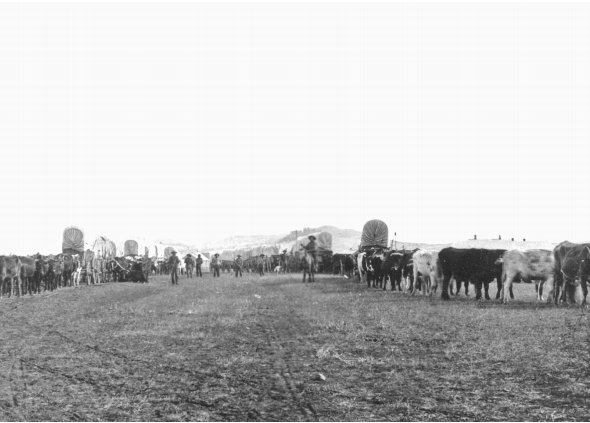

Those men and supplies traveled on bull trains. The bulls, thousands of them in mile-long, meandering trains, had last known civilization in Fort Pierre, two hundred miles to the east. After weeks on the harsh prairie of the Sioux, the exhausted convoys appeared out of the prairie dust, each team of twenty or more oxen pulling sturdy, white-bonneted wagons filled with provisions. Mining and camping equipment—mostly placer pans, shovels, and pickaxes—was gathered up. Rifles were cleaned and pistols were holstered. Information about the overland travel routes was penciled in, and trips were sketched out on the fragile map from the Inter-Ocean News.

Most dream-seekers headed for Deadwood, the spinning hub of the golden excitement; the famous town grew to a population of five thousand almost overnight. It was a lawless place; a gun was judge and jury. Between November 15, 1875, and March 1, 1876, an estimated ten thousand people arrived in the eight thousand square miles of the Black Hills. Five years later, the area’s population would be around twenty thousand, according to the Black Hills Daily Times on February 23, 1884. But the Laramie Treaty soon became a problem.

The Black Hills, and the land over which the miners and other settlers had to travel, did not belong to the United States. Everyone traveling to the Black Hills, and those already in the Black Hills, were trespassing on a sovereign nation’s land and illegally removing its resources. After Custer’s 1874 expedition, this presence of United States citizens in the Black Hills became a problem for the federal government. Try as government forces might, it was impossible to turn back and eject the determined masses clawing and clamoring for gold. For the government to send home those who were already in the Black Hills and to slam the door on those who were on their way was impractical. The hills were like the hub of a gigantic wagon wheel, with supporting spokes all around. The relatively small contingent of soldiers at Fort Laramie, which was more than 150 miles away from the Black Hills, tried to stop the rush, but with a trip of several days between them and the hills and the amount of supplies they would need to maintain a sizeable force there for weeks, it was an impossible task.

There already existed three roads and trails across the Sioux land that had been approved by the tribe in the Laramie Treaty. The treaty also allowed railroad surveyors and construction workers to enter tribal land. Goldseekers were not included on the list of approved visitors, but how could anyone tell one from the other? Perhaps unwittingly, or perhaps because of misunderstandings, the Sioux granted the development of what became three three-mile-wide rights-of-way, which began on the western bank of the Missouri River and crossed their land. Although the treaty denied the United States entry into the Black Hills themselves, the three roads came “near” the forbidden hills. But where could those who traveled the approved roads from Bismarck, Fort Pierre and Yankton, which was known as the Niobrara Route, go after crossing the Sioux land? It was an impossible situation considering the beckoning and constant crescendo of gold.

For the trespassers, the location of the Black Hills in the very center of the Sioux Nation meant they had a long and arduous journey to get to their endowed sanctum. The starting points of the settlers’ journeys, including the three legal eastern roads that were approved in the Laramie Treaty, were located at the four compass points surrounding the Black Hills. The other trails were associated with the parallel continental railroads hundreds of miles to the north and south of the hills. Many goldseekers started their trek from those transcontinental railroads. Others preferred the speed and convenience of taking the train from Sioux City to Yankton and catching a riverboat on the Missouri River to Fort Pierre before heading west on the overland route to Deadwood. Many of these “pilgrims,” as the new arrivals to the hills were called, faced a two-hundred-mile journey over the treaty-approved right-of-way that became the famous Fort Pierre to Deadwood Wagon Trail.

It was by far the shortest route to the Black Hills for the thousands of people, and millions of tons of supplies would soon be pulled by bull train over that challenging, dangerous and deadly road. The road, which was laced with gumbo (sticky mud), became a conveyor belt on wooden wagon wheels that helped keep the Black Hills alive and productive for a decade. By yoking oxen to work in concert with fast horses and muscular mules, settlers were able to carry all the supplies they needed to mine gold and live on the frontier.

The bull trains of oxen that plodded over the Fort Pierre to Deadwood Trail did most of the hard work, hauling hundreds of millions of tons of freight, until eventually the railroad finally punched its way into the hills at Buffalo Gap on the southern slope.

Bull Trains to Deadwood

By Chuck Cecil

Pandemonium wafted up out of Deadwood Gulch whenever bellowing, muddy oxen teams led wagons rattling into town. For a decade, thousands of bull trains hauled all that miners, settlers and ne’er-do-wells needed to survive in that isolated prairie oasis. The bulls, thousands of them in mile-long, meandering trains, had last known civilization in Fort Pierre, two hundred miles to the east. After weeks on the harsh prairie of the Sioux, the exhausted convoys appeared out of the prairie dust, each team of twenty or more oxen pulling sturdy, white-bonneted wagons filled with provisions. Author Chuck Cecil restores the glory of the near-forgotten yet indispensable symbols of the West that made life possible on the frontier’s western fringe.