Natural disasters are unavoidable; but it’s a community’s response to catastrophe that changes and, hopefully, improves over time. When a flood ravaged Virginia in 1870, it inspired a humanitarian response and revealed the limits of local government’s willingness and ability to help its poorest citizens.

“To the ear it sounded as if the elements were holding a concert on the grandest scale of musical combinations. The pattering and silvery tinkle of the millions of rain-drops—the trickling and murmur of thousands of rills—the babbling and splashing of the streams—the roar of the innumerable cataracts, and the sullen, deep, and subdued sounds of the mighty flood and the breaking waves all united in a chorus, that can neither be described nor conceived of in its solemn grandeur.”—Virginia Gazette, October 7, 1870

Disaster Strikes

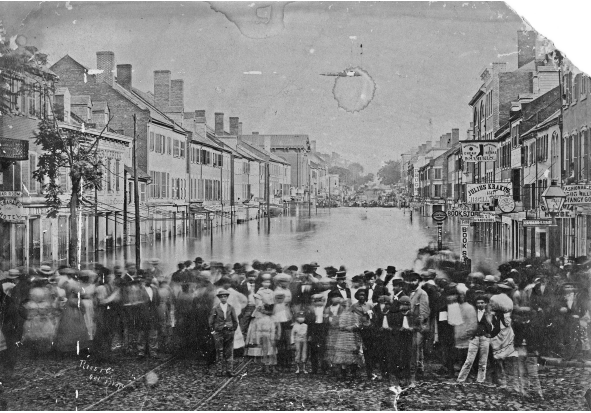

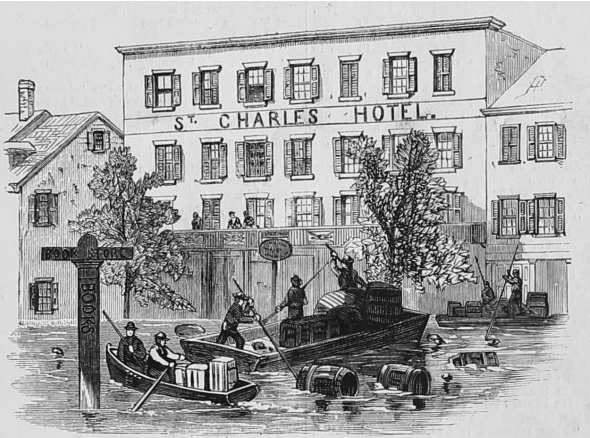

After a long, dry summer, on September 28, 1870, the western part of Virginia witnessed the end of their drought. Not only did the region’s farmers rely on rain for irrigation, but industries including mills and iron furnaces needed running rivers for power. Additionally, shipping and transportation along the inland waterways and canals depended on sufficient water levels. What started as a light rain quickly developed into a massive storm that hung over the region from Wednesday through Friday. The downpour converted the waterways into sweeping torrents. The normally peaceful veins of water became cutting scythes of unstoppable power as the rain brought death, destruction, and economic loss to families and communities that were in the path of the rushing water. Locals sought higher ground, waiting on rooftops or climbing to treetops. Countless were lost.

“Poor women and children were on the streets who had just escaped a watery grave, and every few minutes a low rumble would be heard, the startling signal that one of their once happy homes had sunk beneath the waters together with all their earthly possessions, or perhaps containing loved kindred and friends, whose dying wails could be heard on the midnight air. At intervals all through the night buildings were being swept away.—At one time we heard four fall in less than five minutes.” — Eyewitness at Virginius Island

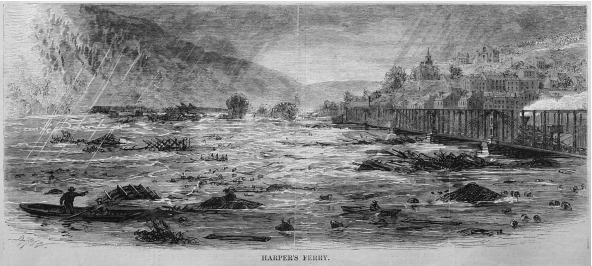

Most of the damage took place near the veins of travel. Once into West Virginia, the flooding continued along a mainly rural path through Jefferson County before reaching the industrialized city of Harpers Ferry, which became the scene of so much death and destruction that it forever left a mark on the town. Where the Shenandoah River meets the Potomac at Harpers Ferry, the flood’s path of destruction turned toward Washington, D.C., sending waves of debris down the river and toward the bridges and shores of Georgetown, Washington and Northern Virginia, finally calming as the river widened and the terrain flattened.

Disaster Relief

What happened to the survivors? What relief did they receive? The First Baptist Church was one of two evangelical churches in Lynchburg that encouraged the wealthy members of their congregations to treat laboring whites as “moral and spiritual equals.” Flood victims were represented, but only after newspapers ran their stories. Virginia’s official plan for relief grew out of an appeal published four days after the flood by John D. Imboden, who publicly appealed for relief in the New York Herald. He sought to bundle donations from organizations in New York City and send them directly to the Virginia governor’s office. Six days after the Imboden letter was published in the New York Herald, Governor Walker called for the Virginia legislature to organize a joint committee to collect and distribute aid, public pressure helped the cause too.

“The Valley of Virginia is ravaged as cruelly as though fire and sword had once more visited it; along the James and the Potomac, there is such distress as has not been since the dark days of the rebellion. A calamity like this should be the means of showing that we know no political differences in the presence of distress. The Quaker’s formula of “How much do you sympathize with them?” will suit the present case admirably, and before many days are over, ought to find a response from the wealth and commerce of this State such as will convince Virginia how truly we sympathize with her in this hour of deep misfortune.” — The New York Times

The Virginia Legislative Relief Committee was composed of three senators and five representatives chosen from areas most affected by the flood. Three weeks after the waters abated, the official plan called for localities around the state to set up relief committees to solicit donations.

Legacy

None of the victims could rely on flood insurance, social aid programs and official policies for dealing with disasters, so commonplace today. At the time of the The Great Virginia Flood of 1870, permanent federal aid programs or professionally organized relief groups didn’t exist, and it would be another 19 years before the Red Cross was formed. Sadder still, it would be another 108 years before the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) came into being.

The Great Virginia Flood of 1870

By Paula F. Green

In the fall of 1870, a massive flood engulfed parts of Virginia, West Virginia and Maryland. What began near Charlottesville as welcome rain at the end of a drought-plagued summer quickly turned into a downpour as it moved west and then north through the Shenandoah Valley. The James, Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers rose, and flooding washed out fields, farms and entire towns. The impact was immense in terms of destruction, casualties and depth of water. The only warning that Richmond, downriver from the worst of the storm, had of the wall of water bearing down on it was a telegram. In this account, public historian Paula Green details not only the flood but also the process of recovery in an era before modern relief programs.