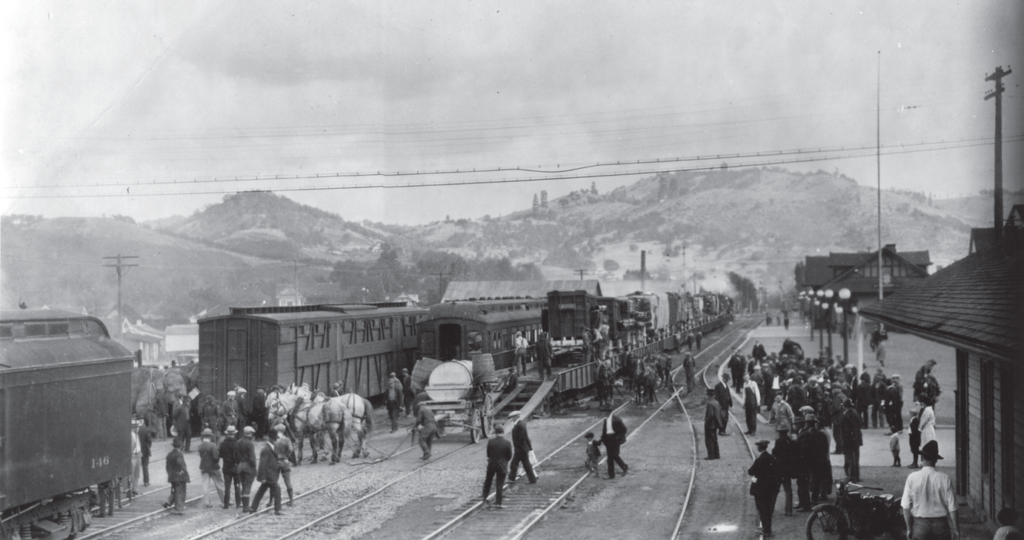

Just before dawn, on June 22, 1918, a train chugged toward Hammond, Indiana. The engineer had drifted asleep, and he did not see that his train was bearing down on another, idle train. The two trains collided, leading to fires, explosions, and the death of eighty-six people. It was one of the worst train wrecks in American history, but it was also one of the strangest. Because those idle cars weren’t just any normal train—they were the train of the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus.

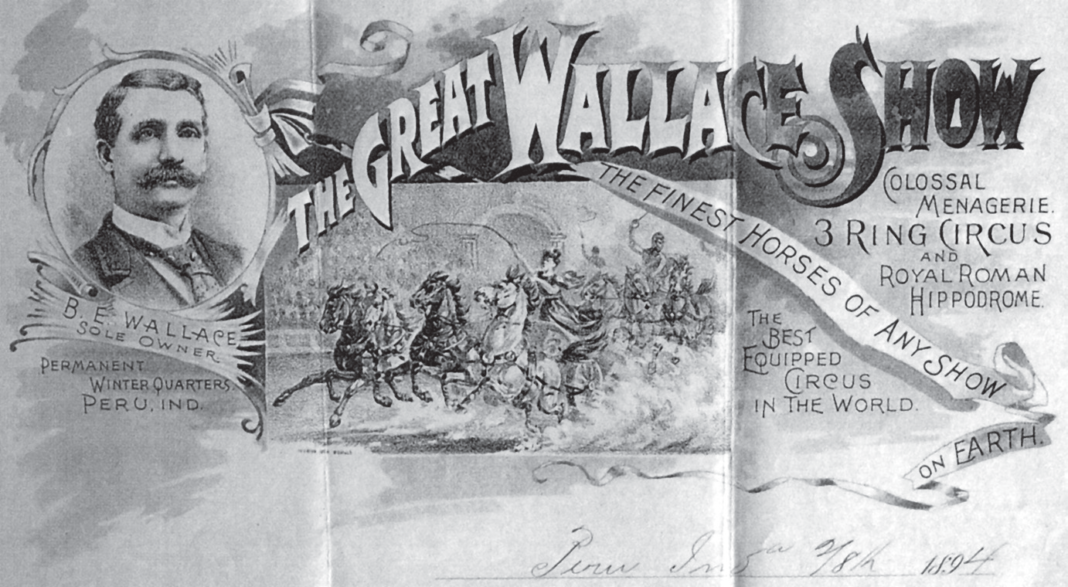

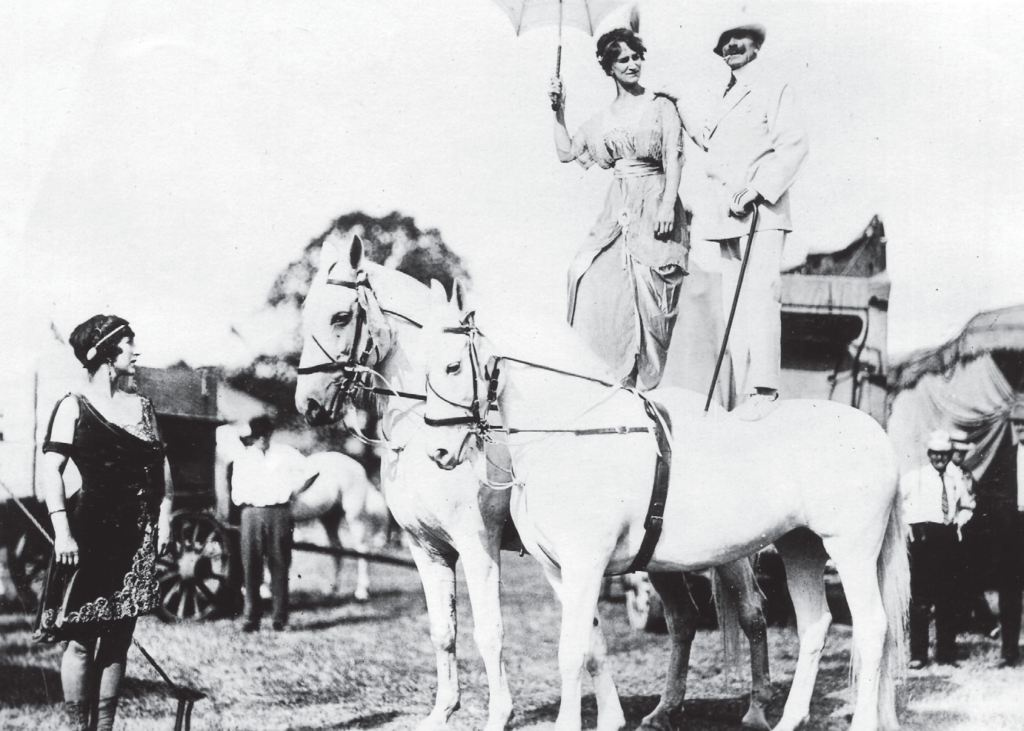

The Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus featured a number of famous performers, including the Cottrell-Powell English bareback riders and the Flying Wards, who specialized in a stunning high trapeze act. They traveled the country and were incredibly popular in the first part of the twentieth century.

To transport all of those performers, in addition to the animals and workers and big-top tent, the Circus traveled by train.

On June 22, that train was sitting idly when it was slammed by more than 150 tons of onrushing engine. In an instant, incoming locomotive began grinding and breaking everything in its path. Wall- and floorboards, frame timbers, bunks, fixtures, dividers, bedding and people were all added to that rolling mass of destruction. Some things and people were tossed aside, but most became part of the debris.

The wreck was terrifying for everyone involved. One story is Mayme Ward’s of the Flying Wards. Mayme was suddenly jolted out of a deep sleep. For one fleeting moment, she felt as if she were a contortionist. While she was on her back, her mattress had folded tightly and completely back; she was painfully aware that her feet were clear above her head, and she was in a rigid and immobile position. She heard someone ask in a strangled tone, “You all right?”

Mayme answered that she was and then said, “But I can’t move.”

Read more: The Great Circus Train Wreck of 1918: Tragedy on the Indiana Lakeshore

With the help of that person, Alexander Todd, she gradually was able to work her way out into the car’s aisle. A moment later, Todd also wriggled free. The floor was a mess of jagged splinters, but they did not notice it at the time. The roof of the car had slid down on their side, crushing the upper berth onto them.

Then Mayme heard a voice from above them saying, “Give me your hand. I’ll pull you up.” It was Charley Rooney, one of the bareback riders. As she went up, her long braided hair caught on projecting fragments of wood. “I didn’t know you were so heavy,” Rooney panted and then harshly jerked her up. Her hair parted company with her scalp, and she was suddenly up in the cool night air.

In the dim dawning light, she stared at chaos, utter chaos. Theirs was the fourth car from the end, not counting the caboose. Where were the other cars? What was all this mass of steel and smoke—and what was that ominous red glow that was beginning to crackle like a wooden bonfire? A numbing flash of pain struck Mayme, and she looked down at her feet. Every toe was dislocated; no two pointed in the same direction.

Todd pushed her roughly. “Get up that way,” he gestured urgently, “and take care of yourself.” He then disappeared into the smoke, steel and sudden flames, paying no heed to the glass that slashed savagely at his bare feet. He was looking for his wife, in the berth opposite theirs. Shortly he found her and stumbled free of the debris with her limp, dead body in his arms.

Nearly ninety people died in the wreck, and close to two hundred were badly injured.