The Stamp Act, which Great Britain passed in early 1765, went into effect 255 years ago this week. Many Americans know the name — and know that it was an important escalation on the way to the colonies revolting against Great Britain.

But what’s less well known is the group behind the Stamp Act backlash, the so-called Loyal Nine. They led the way on a series of protests that was effective, even if it was not exactly peaceful.

Taxes, taxes, taxes

George Grenville, prime minister of Great Britain, was adamant that the colonists help to pay the heavy expense of administering the North American colonies and decrease the debt caused by the French and Indian War. One attempt was the Sugar Act, but that tax alone wouldn’t solve the problem, so the Stamp Act was Grenville’s next solution.

RELATED: How the British Lost the Battle for Fort Ticonderoga READ NOW>

It decreed that any printed documents now needed a stamp, which resembled a notary more than a postage stamp. Newspapers, deeds, diplomas, marriage licenses, playing cards, almanacs and liquor licenses all needed these new stamps. Adding to Bostonians’ annoyance, various items were taxed differently, with over forty tax rates. For example, appointments to public office were subjected to the highest tax, and items written in any language other than English were taxed double the standard rate.

Bostonians heard about the Stamp Act in May 1765, and it was to take effect on November 1, 1765. This six-month lead gave them time to prepare an adequate response before the stamps could be distributed.

First, words

Boston’s rebels first reacted to the Stamp Act in much the same way as they had the Sugar Act: by claiming that it violated their rights under the British Constitution. In September 1765, a Boston town committee wrote a petition that claimed “the most essential Rights of British Subjects are those of being represented in the same Body which exercises the Power of levying Taxes upon them.”

It wasn’t just that rebel leaders didn’t want to pay the tax. (Although that was surely part of it.) They believed that being taxed by a governing body—in which they were not represented—violated their rights as British subjects.

Boston’s petition outlined another legitimate fear: Bostonians consenting to this tax would “afford a Precedent for the Parliament to tax us, in all future Time, & in all such Ways & Measures.” If they paid this tax now, they questioned whether the British Empire would

ever stop taxing them.

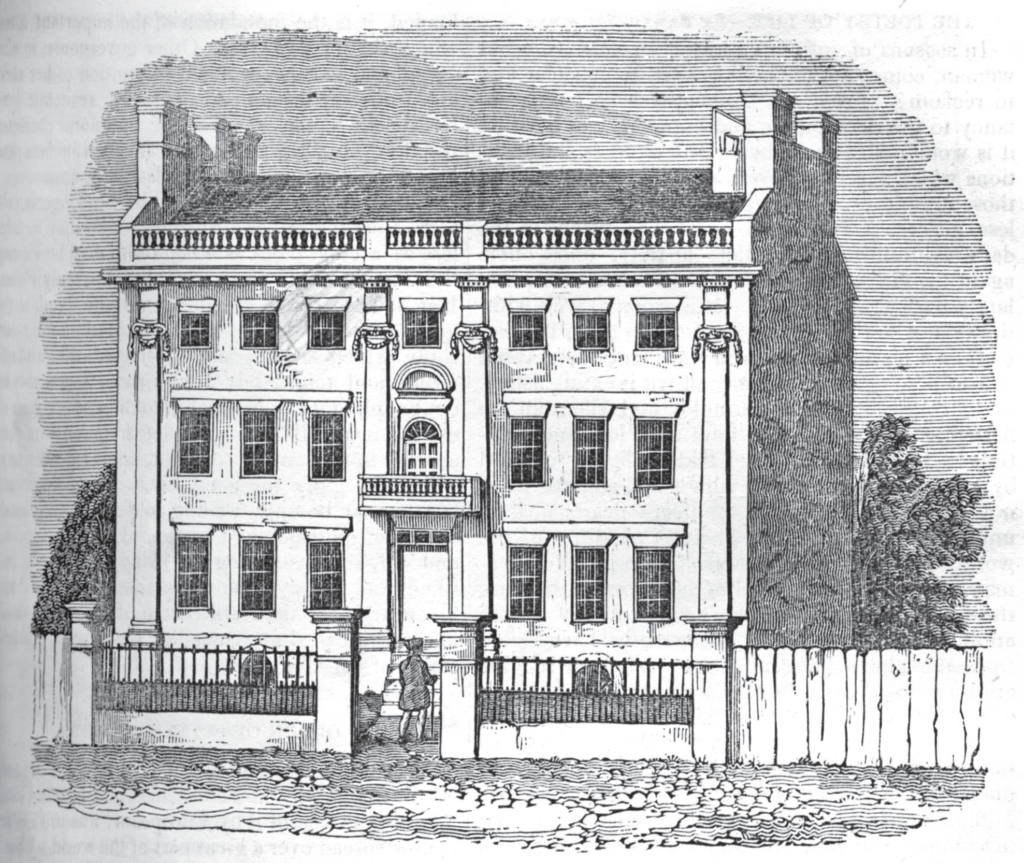

Newspaper editorialists criticized it, lawyers argued that it wasn’t constitutional and ministers condemned it during their sermons. The responses in Boston against the Stamp Act were so intense that Massachusetts lieutenant governor Thomas Hutchinson feared the Stamp Act might lead to violence. “I hope we shall be able to keep peace in the execution of the stamp act notwithstanding all the newspaper threats,” he wrote to a contact in London in August of 1765.

The Stamp Act prompts action

The Loyal Nine was a social club in Boston consisting of nine men in their twenties and thirties, mostly artisans and shopkeepers. This group would eventually evolve and expand later in the year to become the Sons of Liberty, which was filled with names more recognizable to us today: Samuel Adams, Paul Revere, John Hancock and John Adams.

The Loyal Nine’s first target was Stamp Act collector Andrew Oliver. Oliver and Hutchinson were brothers-in-law, as their families frequently intermarried—solidifying both families’ political and economic status and incurring the resentment of Bostonians.

The Loyal Nine enlisted the help of two local, rival street gangs—one from the North End and one from the South End—to intimidate British officials. To fully realize who these men were, know that they got together annually on Pope’s Day, November 5, and participated in an enormous street brawl. The fight occurred under the guise of capturing the other side’s pope, a figure made from papier-mâché, but the point was to rumble.

Bones were broken in the process and gashes earned; even a small child was accidentally killed during the 1764 Pope’s Day fight. This fracas always happened downtown, in plain view of nonparticipating townspeople, demonstrating a tradition of street violence. The leader of the South End gang, Ebenezer Mackintosh, recruited these tough and aggressive fighters, who included rope workers and longshoremen, to work together, instead of as separate gangs, to resist the Stamp Act.

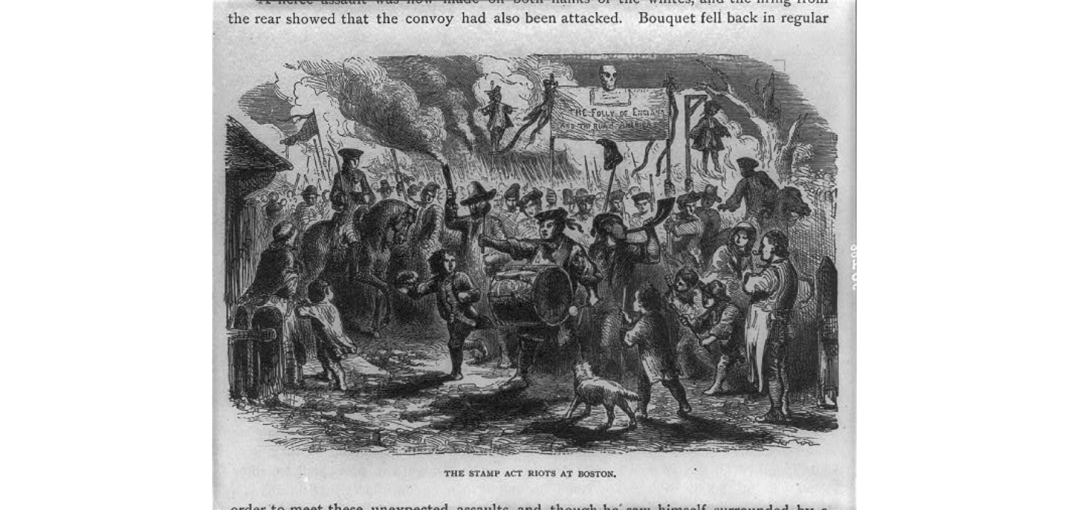

With the mob now in place, Boston became the first town in the North American colonies to rebel violently against the Stamp Act. Because orchestrated violence was an established part of Boston’s political and cultural landscape, mobs opposing an unjust tax were unlikely to face much resistance on the streets. The mob not only sought to embarrass Oliver but also to make it difficult and undesirable for him or anybody else to enforce the Stamp Act. On August 14, a mob hanged Oliver in effigy from a massive elm tree at the edge of town, visible on the main road in and out of Boston. This tree would later be known as the Liberty Tree.

People coming into Boston even stopped to have Oliver’s effigy mockingly stamp their goods. In the evening, the mob paraded through Boston and, as Governor Bernard noted, passed by “the Town House, bringing the Effigy with them, and knowing we were sitting in Council Chamber, they gave three Huzzas by way of defiance, and passed on.”

But the mob was just getting warmed up.

Discover more….

In 1764, a small town in the British colony of Massachusetts ignited a bold rebellion. When Great Britain levied the Sugar Act on its American colonies, Parliament was not prepared for Boston’s backlash.

For the next decade, Loyalists and rebels harried one another as both sides revolted and betrayed, punished and murdered. Samuel Adams and John Hancock were reluctant allies. Paul Revere couldn’t recognize a traitor in his own inner circle. And George Washington dismissed the efforts of the Massachusetts rebels as unimportant. Historian Brooke Barbier tells the story of how a city radicalized itself against the world’s most powerful empire and helped found the United States of America.