Galveston, the island city on the Texas Gulf Coast, has long been seen as the “Playground of the Southwest.” Its beaches call out to tourists and conventioneers, who come ready to play. Where fun unfurls, vice follows.

In the early 20th century, Galveston’s official and unofficial leaders sought to manage gambling and prostitution by limiting it to a few blocks know as the Line, and essentially “looking the other way.”

Pirate Jean Lafitte

Forced to retire from New Orleans, Lafitte brought his band of privateers to Galveston, and found the native Karankawa women to be irresistible. They sought the company of the plundering sailors, who plied them with jewels. The Karankawa men objected and fought the Lafitte camp over the women. Both pirates and natives disappeared as Mexican control increased on the island in the 1820s.

Madam Mary “Gouch-Eye” Russel

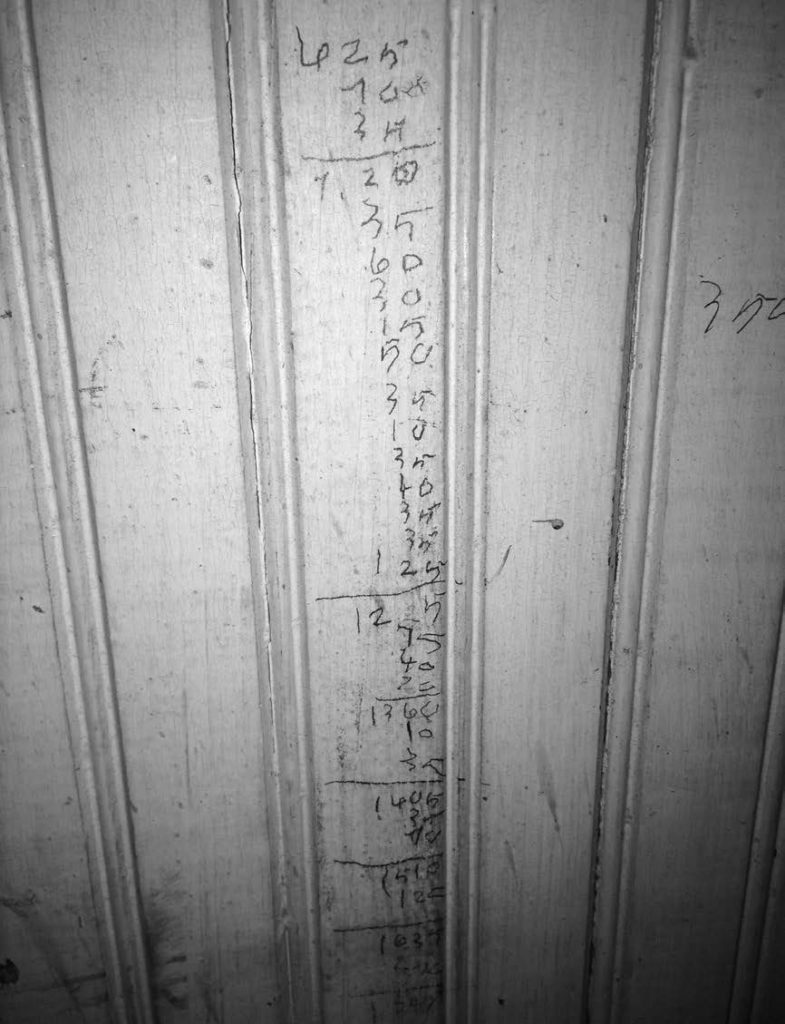

Russel who ran a bordello for over two decades, partnered with the mayor whenever he needed a special girl for a visiting big-shot. His gratitude was repaid when she would be tipped off to law enforcement house raids, which were mostly for show only. Within the boundaries of the Line, bordellos served johns and kept prostitution off the streets. At their peak in the 1940s, some houses could earn as much as $20,000 in a week!

“They had only one thing to sell, but they knew the law of supply and demand; as far as they were concerned, that was the only law that mattered.”

Ruth Levy Kempner

Kempner married into one of Galveston’s most prestigious families. She had progressive and pragmatic views that sex workers would ply they trade no matter what, so why not have a little oversight by the cops? Never a prissy or hypocritical Victorian, Kempner stood up to conventional thinking as an advocate for prostitutes. She was also fearless, standing up to corrupt law enforcement officials, who profited from shaking down underworld figures, madams, and even prostitutes themselves. In 1961, her endorsement from famed madam Big Tit Marie probably won Kempner election to city government.

Crusaders were hell bent on 86ing prostitution altogether, and would close the Line periodically. When vice pushed back underground, it corrupted the cops, who were susceptible to bribes. Mayoral candidate Roy Clough resisted the crusaders, knowing the economic value the illicit activities brought to the city; and, like Ruth Kempner, encouraged the red light district’s “out-of-sight, out-of-mind” philosophy. He reasoned that bribed cops were worse than monitored, behind-closed-door vice. He reopened the Line, but state officials, tired of the embarrassing national headlines, wore down his political support. Clough served from 1955 to 1959.