This is Part 3 in our continued series, Healthcare Heroes, where we look back at the profound legacy of American doctors, nurses, and healers.

Self-Proclaimed or Actual Doctor?

In 1789, the new United States Constitution was ratified and George Washington was chosen as president. While Charleston rice and indigo planters scrambled to restore their fortunes by planting cotton after the war, a handful of doctors gathered in 1789 to form the Medical Society of South Carolina.

At that time, anyone who wanted to call himself a doctor or to practice medicine was legally permitted to do so. But the issue of who could call himself a doctor grew more important to those few who had obtained a medical education.

Charleston was home to a number of formally educated doctors. William Bull and John Moultrie Jr. were the two earliest Charleston doctors who had actually received formal medical degrees, from universities in the British Isles. One of the reasons these doctors founded the medical society in Charleston was so that patients could identify those doctors who had certified training.

Read More: Healing All People: The Roper St. Francis Healthcare Alliance by Jane O’Boyle

In 1817, the state legislature mandated doctors’ regulations and licenses and, in 1820, extended licensing to apothecaries. But the society’s self-proclaimed greatest achievement to date occurred in 1824. The Medical Society inaugurated the Medical College of South Carolina, with lectures by Dr. Philip Gendron Prioleau in anatomy, surgery and midwifery, and Dr. Benjamin B. Simons in chemistry.

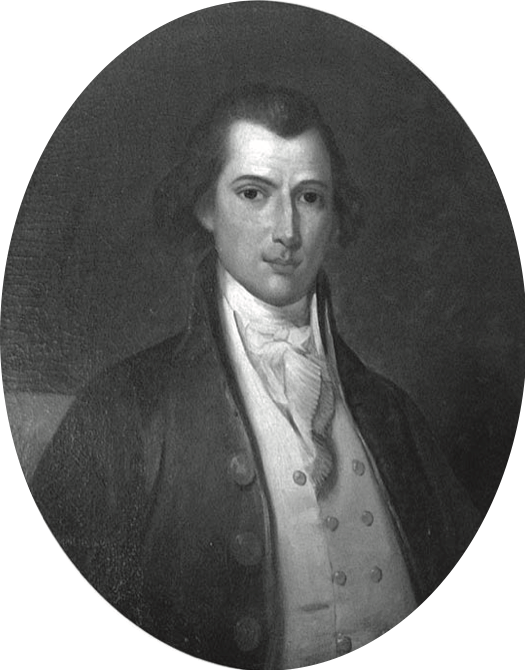

Mr. Thomas Roper and His Legacy

Mr. R.W. Roper died on June 12, 1845, and, as he had no children, his estate was dispensed as his father’s will had instructed back in 1829. His father was the former mayor, Colonel Thomas Roper, who had stipulated that, without heirs, the estate would go to the Medical Society of South Carolina. Colonel Roper’s other son, Dr. Thomas W. Roper (R.W.’s brother), had once been secretary for the Medical Society but had died in 1817.

In honor of his son, Colonel Roper had outlined that without other grandchildren, the society would use the endowment to build a hospital in Charleston. This was when the society established the Roper Fund, with the Roper bequest of approximately $30,000.

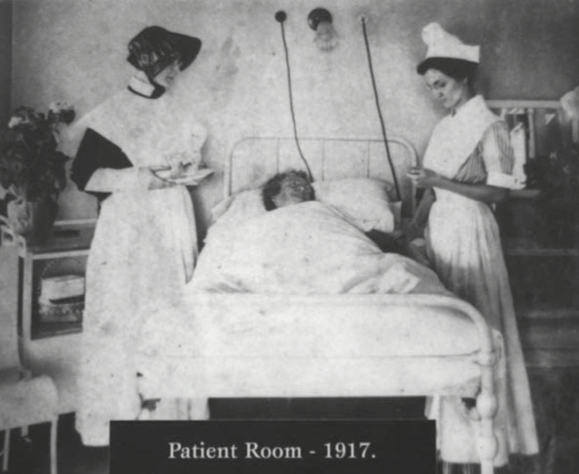

The first Roper Hospital opened in 1856 and was managed by the City of Charleston. That same year, 254 patients were treated there for yellow fever, of whom 92 died. During what the minutes call the War Between the States, the Union army controlled the city of Charleston after the siege and commandeered Roper Hospital for its wounded soldiers. After the war, the 1886 earthquake destroyed the Queen Street building, and it was abandoned after only thirty years.

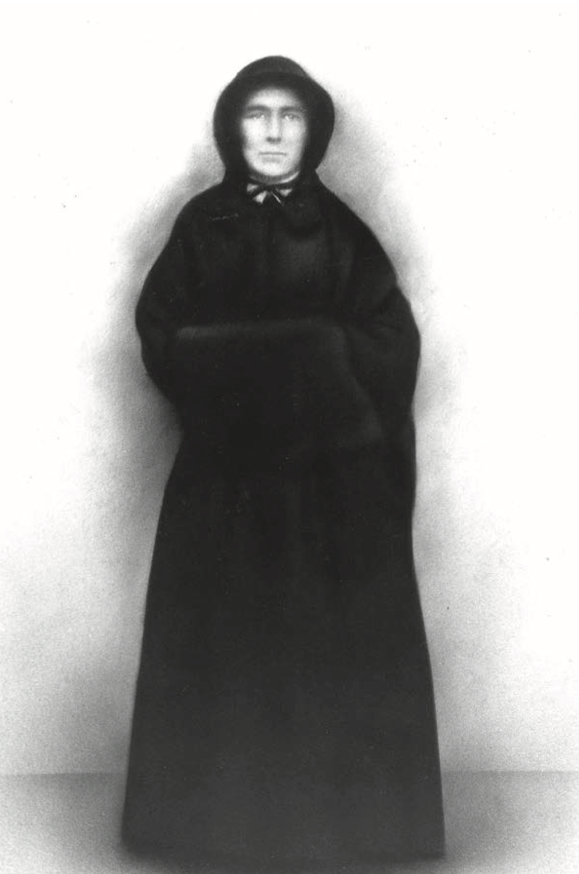

The Sisters of Charity of Our Lady of Mercy

The Sisters of Charity of Our Lady of Mercy were founded in Charleston in 1829 with the primary mission of pastoral care. Organized by Bishop John England, the sisters ministered to the sick in Charleston homes. Yellow fever and cholera epidemics were a regular occurrence.

Sister Xavier and her superior, Mother Teresa Barry, pleaded to the bishop for a Catholic hospital in Charleston. But it was the gift of Charlestonian Maria McHugh that made it happen when she gave the sisters a large brick house on Magazine Street. The sisters sold this house and bought a property on the northeast corner of Calhoun and Ashley.

Read More: Healing All People: The Roper St. Francis Healthcare Alliance by Jane O’Boyle

In 1900, the hospital opened a school of nursing at St. Francis. New buildings were added throughout the 1900s.

Mary McKay and Beulah Manigault

In the aftermath of Hurricane Hugo, the night shift nurse supervisor, Mary McKay, moved into an eighth-floor hospital room at the St. Francis high-rise on Rutledge and Calhoun. Her home had been devastated during Hugo, as had so many, and there was much for her to do at the hospital. McKay was known for her meticulous makeup, and her room at the hospital had a pink floral wreath on the door that read “Mary’s Room.” She was a diminutive, beloved fixture at St. Francis ever after, ushering homeless transients inside during cold winter nights. She didn’t move out until the hospital moved west of the Ashley, on which occasion she retired to the Canterbury House.

McKay was soon followed into retirement by Beulah Manigault, a St. Francis nursing assistant on St. Gerard’s Hall for thirty-four years. Manigault had worked the 3:00 p.m. shift and raised four daughters with her husband, Harold, in their home at Smith Street and Vanderhorst. “Ms. McKay had no family, so I took care of her too,” said Manigault. “We were her family.”

St. Francis was the first hospital to become integrated in those years, and Manigault was hired by Sister Emmanuel. She cleaned bedpans, changed sheets, sterilized utensils and brushed teeth for the genteel ladies in her ward of private rooms. There was one bathroom at the end of the hall for those fifteen patients, and it had no sink and no tub. “The nurses were so good to me at that time,” said Manigault. “Mary McKay, Anne Moore. They were like family.”

Two decades later, Manigault visits McKay daily and helps with her hair and makeup.

Buy the Book: Healing All People: The Roper St. Francis Healthcare Alliance by Jane O’Boyle