Theodore Roosevelt is often called the “father of conservation.” As president, he authorized the creation of 150 national forests, 18 national monuments, 5 national parks, 4 national game preserves and 51 federal bird reservations.

But Roosevelt’s role in the conservation movement got a crucial boost in 1903, when he went on an epic three-day wilderness adventure at Yosemite with naturalist John Muir.

Meeting Muir

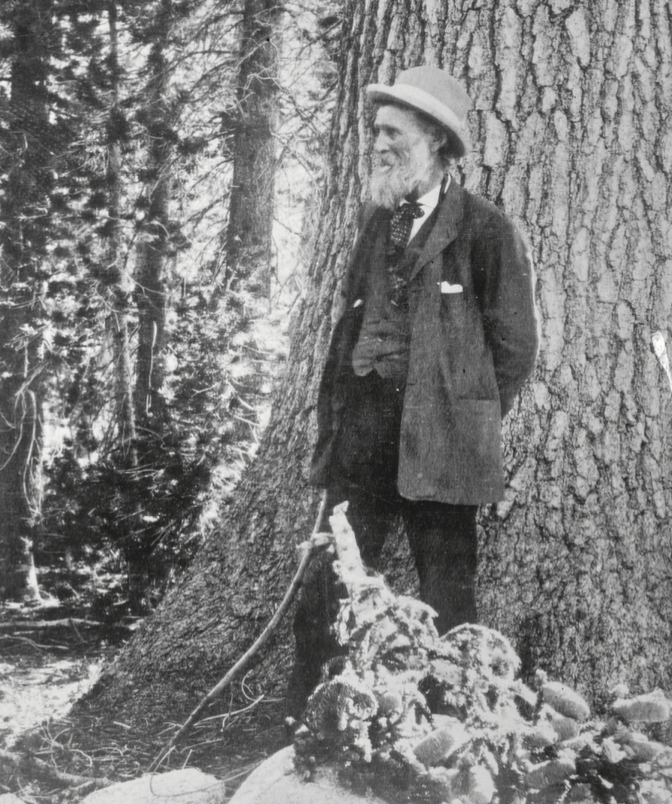

While the turn of the century was a time of urbanization and concentrated wealth, it was also a time when Americans began to appreciate their shared treasure: the great outdoors. John Muir was an important conservationist and author who had founded the Sierra Club.

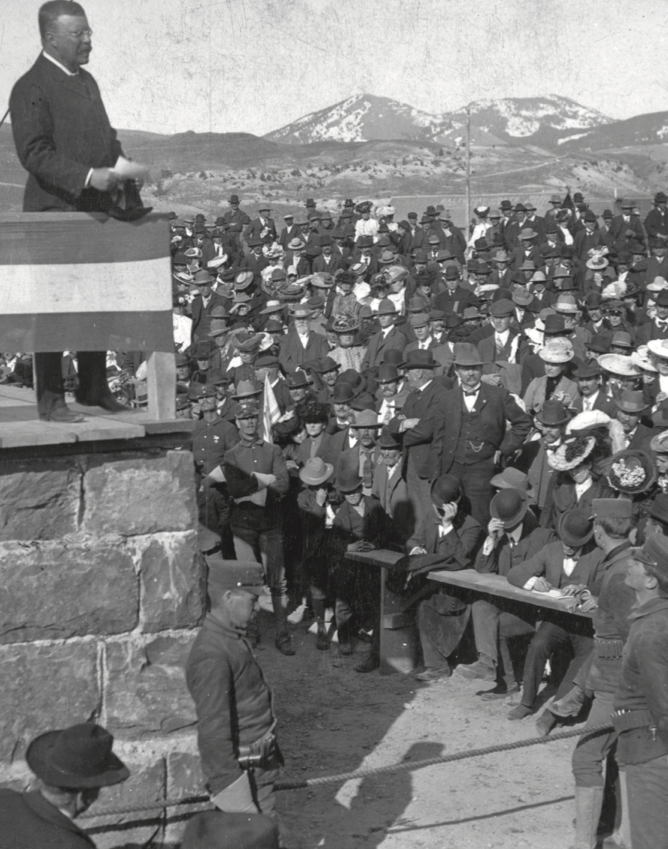

Roosevelt had read Muir’s writings closely, and through California senator Chester Rowell, he communicated to Muir an interest in meeting with him in Yosemite and away from the main party of dignitaries. “I do not want anyone with me but you,” the president wrote in 1903, “and I want to drop politics absolutely for four days and just be out in the open with you.”

The rest, as they say, is history.

Three Days at Yosemite

That spring, the two men went on their trip. The best account of their camping remains Roosevelt’s:

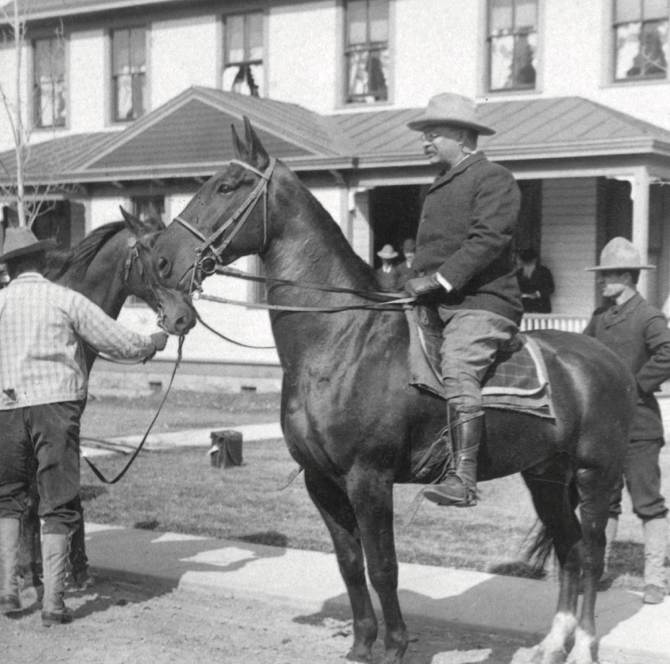

He met me with a couple of pack mules, as well as with riding mules for himself and myself, and a first-class packer and cook, and I spent a delightful three days and two nights with him.

The first night we camped in a grove of giant sequoias. It was clear weather, and we lay in the open, the enormous cinnamon-colored trunks rising about us like the columns of a vaster and more beautiful cathedral than was ever conceived by any human architect. One incident surprised me not a little. Some thrushes—I think they were Western hermit-thrushes—were singing beautifully in the solemn evening stillness. I asked some question concerning them of John Muir, and to my surprise found that he had not been listening to them and knew nothing about them. . . . Muir, I found, was not interested in the small things of nature unless they were unusually conspicuous. Mountains, cliffs, trees, appealed to him tremendously, but birds did not unless they possessed some very peculiar and interesting as well as conspicuous traits, as in the case of the water ouzel. In the same way, he knew nothing of the wood mice; but the more conspicuous beasts, such as bear and deer, for example, he could tell much about.

All next day we traveled through the forest. Then a snow-storm came on, and at night we camped on the edge of the Yosemite, under the branches of a magnificent silver fir, and very warm and comfortable we were, and a very good dinner we had before we rolled up in our tarpaulins and blankets for the night.

The Trip’s Legacy

That brief camping trip proved to be a game changer for the wide-eyed president who loved the rugged great outdoors and would soon, thanks to Muir, work even harder to protect it.

After Muir died, Roosevelt wrote a remembrance of him. “He was emphatically a good citizen,” the president wrote. “He was also—what few nature lovers are—a man able to influence contemporary thought and action on the subjects to which he had devoted his life.”

The same could be said of Roosevelt, especially on issues of conservation. How incredible it is, then, two imagine these two nature lovers spending a few nights at Yosemite, camping beneath the stars.