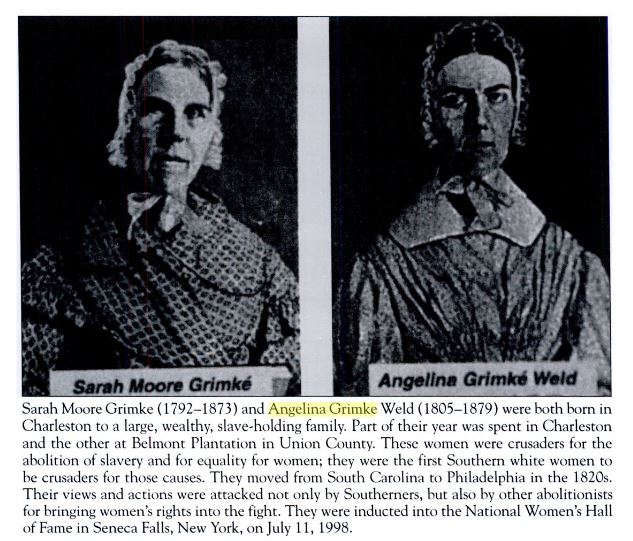

Sarah Grimke (1792-1873) and Angelina Grimke Weld (1805-1879) were two sisters born 13 years apart who shared the deep-seated belief that slavery was not a condition which any human should have to abide. In their fight to end slavery, they came to be strong believers in the importance of equality between men and women, thus becoming prominent speakers for women’s rights as well. Read on as we delve into the lives of two women who were early and prominent activists for abolition and women’s rights.

The Early Years

Sarah and Angelina were both born on a slave-holding plantation in South Carolina just 13 years apart. Unable to attend law school as her brother had, Sarah declared her devotion to her sister at her birth, vowing “to guide and direct [this] precious child.” This commitment foreshadowed the lifelong bond the sisters would share and strengthened them in their fight for abolition. As Sarah had developed an antipathy towards slavery early on, it only stands to reason that she would guide Angelina to be similarly disposed.

The Grimke sisters, as they were commonly known, grew to despise slavery, witnessing its cruel effects first-hand from a young age. Their father, Judge John Fauchereaud Grimke, had 14 children total, both African-American and white, and held them all to the highest standards of discipline. Sarah later recalled that her father sometimes required them to work in the field shelling corn or picking cotton. She observed “Perhaps I am indebted partially to this for my life-long detestation of slavery, as it brought me in close contact with these unpaid toilers.”

Both sisters could have enjoyed the conveniences and luxuries life in Charleston had to offer, as the daughters of a wealthy judge, yet chose another path. The injustices and immense suffering they observed on the plantation imbued a personal sense of responsibility to put an end to slavery.

Quakerism & Philadelphia

In 1819, Sarah accompanied her father to Philadelphia for medical treatment. While there, she encountered members of the Society of Friends, also known as Quakers, who helped her care for her dying father. After his passing, she returned to Charleston, where her feelings against the practice of slavery were resolved: “…after being for many months in Pennsylvania when I went back it seemed as if the sight of [the slaves’] condition was insupportable…can compare my feeling only with a canker incessantly gnawing…. I was as one in bonds looking on their sufferings I could not soothe or lessen….” In spite of her family’s opposition, Sarah converted to Quakerism and moved to Philadelphia in 1821. Her sister, Angelina, followed in 1829.

While most residents of Philadelphia did not share Angelina’s opinions on slavery, she was able to find a small circle of abolitionists who did. Encouraged by the call of male abolitionists for women to become involved, she began attending anti-slavery meetings and quickly became an activist in the movement. In 1835, disturbed by riots against abolitionists and African-Americans, Angelina was prompted to write a personal letter to William Lloyd Garrison, publisher of an appeal to all Boston citizens to repudiate all mob violence. In her letter she said, “The ground upon which you stand is holy ground,” she told him, “never-never surrender it . . . if you surrender it, the hope of the slave is extinguished.” Agitation for the end to slavery must continue, Angelina declared, even if abolitionists are persecuted and attacked because, as she put it, “This is a cause worth dying for.”

Not thinking to request permission in advance, Garrison published Angelina’s letter. Though she was embarrassed, this publication launched her career as a public figure; her life would never be the same.

Life in the Spotlight

Angelina and Sarah became agents for the American Anti-Slavery Society shortly thereafter. They toured churches throughout New York as vocal yet persuasive advocates of abolition. Angelina was quickly recognized for her powerful skill as an orator, often surpassing her male counterparts who were also touring the reform lecture circuit.

After some time lecturing in New Jersey, the sisters returned to New York, speaking for the first time to a mixed-gender crowd. Though skeptics warned that two women speaking together could damage the anti-slavery cause, their first tour was largely regarded as successful. From there they shared an exhaustive tour of New England, furthering the abolition movement. As of 1837, there were no longer gender restrictions on the audience.

An Historic Speech

In 1838, the day after her 33rd birthday, Angelina made history once again, as the first woman to speak before a legislative body in the United States. The Grimke’s notoriety was such that the State House was brimming with people eager to hear her speak. After presenting the petitions, signed by an estimated 20,000 women, Angelina said, “I stand before you as a southerner, exiled from the land of my birth by the sound of the lash and the piteous cry of the slave. I stand before you as a repentant slaveholder. I stand before you as a moral being and as a moral being I feel that I owe it to the suffering slave and to the deluded master, to my country and to the world to do all that I can to overturn a system of complicated crimes. . . .”

Though the content of her initial message was expected, she went on to say, “the great and solemn subject of slavery. . . . Because it is a political subject, it has often tauntingly been said, that women had nothing to do with it.” She forcefully insisted that “American women have to do with this subject, not only because it is moral and religious, but because it is political.” As such, she effectively became one of the very first to make public claims about women’s political rights, thus solidifying her representation in history as an advocate of both abolition and women’s rights.

Marriage & Death

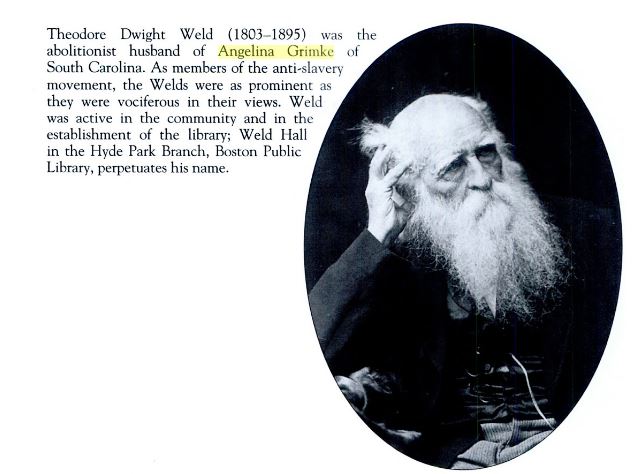

Throughout her work as an abolitionist, Angelina had become acquainted with the abolitionist leader Theodore Weld, also known as “the most mobbed man in America.” A few months after her historic speech, on May 14, 1838, Angelina and Theodore were wed. Angelina was then banished from her Quaker life as a married woman, as was Sarah, for attending the wedding. Two days later, Angelina addressed the crowd at the anti-slavery convention in Philadelphia for the last time. The next morning an angry mob surrounded the building, setting fire to it in the evening, destroying all the books and records they could find.

Though her career effectively ended that night in Philadelphia, Angelina continued to write, alongside her husband, Theodore. Over the next few decades the sisters and Weld earned a modest living as teachers, often in schools established by Weld himself. When the Civil War came, Angelina realized the need for force in the fight for abolition, and strongly supported the Union effort.

Sarah Grimke died at the age of 81 and was followed by her sister 6 years later, dying in 1879. Theodore Weld survived another 6 years, dying in 1895. The three all saw the end of slavery before their respective deaths, as well as the rise of the women’s civil rights movement. Any student of abolition and suffrage recognizes her role in achieving both.

Were you familiar with the story of the Grimke sisters? Comment below.

For more on the Grimke sisters, consider the resources in which they are mentioned below.

Palmetto Women: Images from the Winthrop University Archives

Boston and the Civil War: Hub of the Second Revolution

Stories from Perth Amboy

Charleston: 1900-1915

Brooklyn’s Plymouth Church in the Civil War Era: A Ministry of Freedom