Every city, town, parish, community and school has their own paranormal history. Whether they are spirits caught in the Bardo, ancestors checking on their descendents, restless souls attempting to send a message to those on the living side of the veil, or simply toublemakers taking joy in giving living-kind a scare, ghosts have been part of the human tradition from the beginning of time.

In this book, we feature a collection of stories from five of America’s most haunted cities: Washington D.C., New Orleans, Chicago, Galveston and Baltimore.

Read a sample story from the chapter on Washington, D.C. below.

Get the FREE PDF eBook

Get America’s Most Haunted Cities eBook free when you sign up to receive the Yesterday’s America newsletter.

[mc4wp_form id=”1706″]

THE BLOODY STEPS

Not just congressmen work at the Capitol, so it’s natural that not just congressmen should haunt it. Since the beginning of the republic, people have wanted to get information to their congressmen and people have wanted to get information from them. As such, lobbyists and reporters have wandered these halls since they were built and are no doubt doing it as you read this. Both professions can suffer from a poor public image and they can certainly be relied on as foils when politicians need to blame someone, but both fill a needed role in our system of government. When the cameras are off, it’s not surprising to see a congressman, a journalist and a lobbyist having a drink together.

This is not to say that all three coexist harmoniously at all times—or even peacefully. A particularly violent falling out occurred in the wake of the 1886 election. Democrat William Preston Taulbee was reelected by a narrow margin in the Kentucky Tenth District and was settling in for what appeared to be a tough new term when a story by the Washington correspondent of his hometown Louisville Times, Charles Kinkaid, broke with the headline “Kentucky’s Silver-Tongued Taulbee Caught in Flagrante or Thereabouts.” Kinkaid kept the story alive, and not only did Taulbee choose not to run in the next election, his chosen successor lost as well.

Taulbee did what so many ex-congressmen do and took up lobbying. As such, he came in constant contact with Kinkaid, who was still on the Capitol beat. Taulbee, broad shouldered and a foot taller than Kinkaid, delighted in taunting the scrawny journalist. In February 1890, the two met on the steps outside the House Gallery. Accounts vary as to exactly what words were used, but there’s general agreement that Taulbee taunted Kinkaid again, possibly tweaked his nose and suggested they step outside. Kinkaid responded that he was “in no condition for a physical contest with you—I am not armed,” to which Taulbee responded, “Then you had better be,” or perhaps, more lyrically, “You damned little coward and monkey, now go and arm yourself.”

Either way, Kinkaid left and returned a few hours later. As Taulbee was descending the stairs, Kinkaid called out, “Can you see me know?” As Taulbee turned, Kinkaid shot him in the face. Taulbee initially survived the shooting but died of the wound several days later. Kinkaid was acquitted on the basis of self-defense, and the story faded from memory except for one nagging detail.

To this day, if you walk down the steps on the east side of the Capitol, descending from the House Gallery, you will come across the bloodstains of William Taulbee, permanently staining the marble. No amount of scrubbing has managed to erase them. And if you happen to be a journalist, take particular care. The ghost of William Taulbee likes to trip reporters on this particular flight of stairs.

Get the FREE PDF eBook

Get America’s Most Haunted Cities eBook free when you sign up to receive the Yesterday’s America newsletter.

[mc4wp_form id=”1706″]

Okay, okay – you want another story?

Here’s one from Chicago:

THE SOLDIER’S LOT

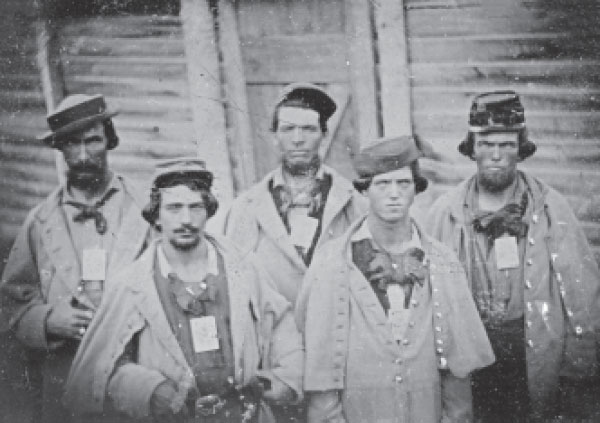

Unidentified Confederate prisoners at Chicago’s Camp Douglas, circa 1865. Photo: Library of Congress.

Few Chicagoans today are aware that the body of Senator Stephen Douglas, the “Little towering monument outside a condominium complex. In fact, Douglas and his wife had made their home at this very spot, on their estate called Okenwald, near Twenty-Fifth Street and Cottage Grove Avenue, and it was here that Douglas was buried after his death in 1866. Plans for the tomb, however, did not come to fruition for more than fifteen years; in the interim, one of the most notorious prison camps in history grew up around it.

Camp Douglas was first founded as a training camp for Union soldiers in the early days of the war, when Chicagoans were chomping at the bit to participate in the conflict. After the capture of Fort Donelson in February 1862, however, more than twelve thousand captured Confederates had nowhere to be housed, and Camp Douglas became a prison camp.

Death was a daily occurrence at the camp, most from diseases like smallpox and scurvy. There was no cemetery on the grounds, and the dead were hastily piled in makeshift burial grounds near the camp or sold to a local undertaker who promised to give them proper burials at Chicago’s City Cemetery in Lincoln Park. Greed on undertaker C.H. Jordan’s part, however, led to the burial of more than three thousand of the camp’s Confederate soldiers in the cemetery’s potter’s field. By the time the order Giant” who campaigned against Abraham Lincoln, is interred on its own on Chicago’s South Side—under a came to close the cemetery and relocate the graves, a good half of them had disappeared in the shifting, sandy loam of the field. In addition, desirable Rosehill Cemetery refused to reinter the Confederate dead within its property. Oak Woods, instead, stepped up to receive the unwanted soldiers for burial on its south side grounds. Earlier, Oak Woods had arranged for reburial of the smallpox victims who had been interred outside the walls of the camp. Two aldermen were awarded the contract to rebury the soldiers from City Cemetery. Witnesses on hand at the reburials claimed that a large number of caskets seemed to be empty. It is now generally believed that the majority of Confederate burials at City Cemetery remain there today, under the ball fields near LaSalle and Clark Streets. Both that expanse and the park built on the former site of Camp Douglas are today rife with ghostly encounters, including tactile sensations of being grabbed by one’s arm or hand, the smell of tobacco and intense spots of cold and feelings of dread or sadness that come and go without reason or warning.

The “Soldiers Lot” at Oak Hill went on to suffer myriad problems with drainage at the site, leading to reports of sunken graves, disappearing markers and, worst of all, claims that buggies and wagons were driving Ghost Stories from the World’s Fair, the Great Fire and Victorian Chicago over a portion of the occupied land. In 1893, a monument was erected by former Confederate soldiers, families of the dead and other supporters of the “Lost Cause.” The site continued to deteriorate from drainage problems, and just after the turn of the century, the monument was removed, a mound of dirt piled on top of the graves (including many of the markers) and the monument replaced. The “Confederate Mound” still stands today, a tribute to the bravery of the Confederate dead and their legacy of unrest in their final resting place of Chicago.

After the war, the drive to complete Douglas’s tomb resumed. Despite a hearty wave of support at the laying of the cornerstone in 1866, the needed funds were not forthcoming for the planned structure. When the tomb portion was completed, the body of the “Little Giant” was put in place, but the site soon languished for want of money to complete the monument, the foundation cracking and the surrounding grass overgrown. Douglas’s widow begged authorities to move her husband’s tomb to a more fitting location where it could be cared for, but her pleas went unanswered. Finally, after years of failed funding efforts, the tomb and memorial were completed. But the site would forever retain its reputation as unattended, uncared for and unnoticed.

Sightings of a shadowy male figure in period dress sitting on the ground near the tomb began almost immediately after its completion, causing Chicagoans to wonder if the lack of respect shown Douglas by the funding problems had brought him back from the dead. But the truth was that there were at least two other possibilities for a ghostly visitor here. In November 1877, W.F. Coolbaugh, a well-known Chicago bank president and close personal friend of Douglas’s, shot himself at the monument. He was found prostrate in his own blood with a pistol at his side. Coolbaugh’s family told the press of their patriarch’s long ill health and periods of despondency. He had been cheerful enough lately, they said, but when he did not return home the night before, the men of the family had gone out in search of him until the wee hours.

Two years later, a second man shot himself at the Douglas monument: Martin Arndt was a tailor who had asked for a raise at work on the morning of June 29. The raise was denied and Arndt dismissed from his position for asking. Out of his mind with fear and filled with self-doubt, Arndt realized in a moment of insanity that his union provided suicide benefits to families of its members. He decided to kill himself and, after writing a letter of apology to his wife, made his way to the Douglas monument and shot himself in the chest. He did not die from the first wound and shot himself in the temple.

Occasional tales of that shadowy figure at the monument are still told today.

Get the FREE PDF eBook

Get America’s Most Haunted Cities eBook free when you sign up to receive the Yesterday’s America newsletter.

[mc4wp_form id=”1706″]