Although we today look back on contributors to early American history with a kind eye, the Founding Fathers and their direct successors had their own share of drama while in office. Here are five of America’s most infamous political scandals prior to 1900.

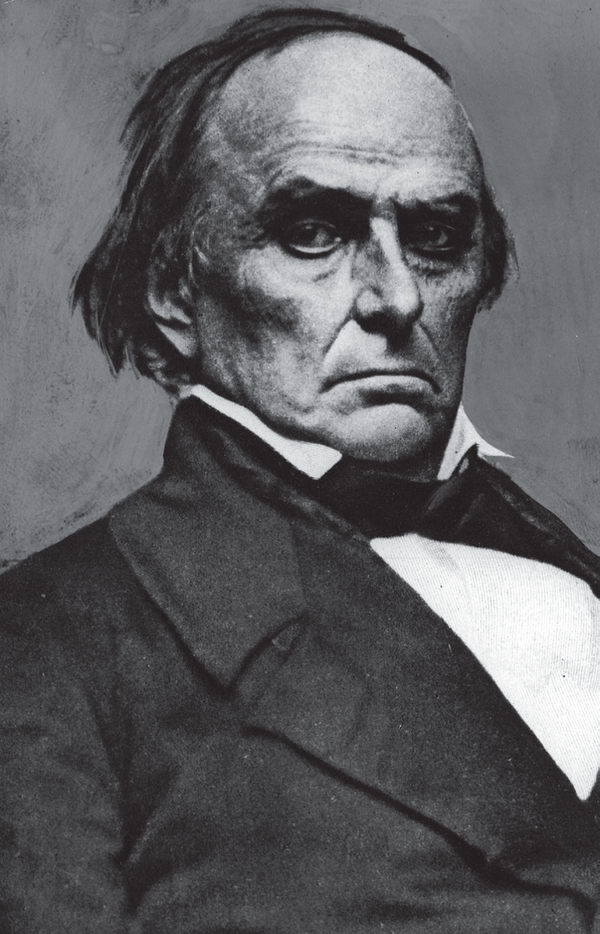

1850: Daniel Webster’s Slave Mistress

By 1850, journalist Jane Swisshelm had managed to do quite well for herself in terms of 19th century – the first woman to hold a position in the Senate press chamber, Swisshelm was an outspoken abolitionist journalist. During the course of her involvement in the press chamber, Swisshelm became aware of rumors that the “Godlike” (as he was often referred to) Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts was involved with a colored slave woman, and had birthed eight children by her. Although several members of the Senate press chamber (and abolitionists) were aware of Webster’s involvement, there was a type of “Gentlemen’s Code” in place, which agreed that journalists would not write about or pry into the personal lives of politicians. However, Swisshelm could not overlook Webster’s hypocrisy, as he had been an ardent opponent against the extension of slavery. Unable to turn a blind eye, she published an exposé on Webster’s behavior, and lost her position within the press chamber as a result. Today, Swisshelm is relatively unknown within American history, while Webster has maintained a revered legacy. His indiscretion is not widely publicized, though Swisshelm did write about her life and career in her autobiography, Half a Century.

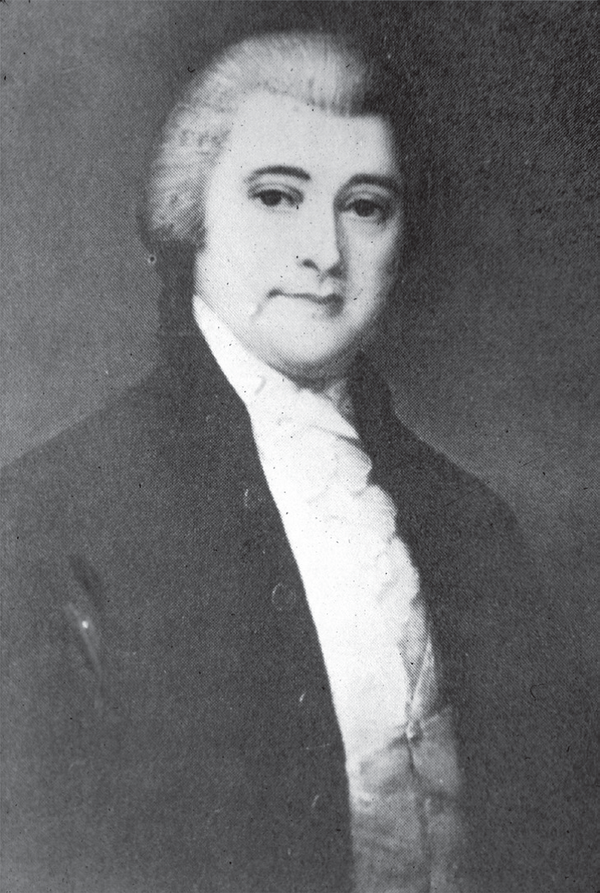

1796: The William Blount Conspiracy

Throughout the 1780s and 90s, statesman and speculator William Blount purchased large amounts of western land in the United States on credit. Although Blount had planned to turn a profit on the lands to repay his debt, the prices for these lands plummeted in 1795, and Blount and his family were left bankrupt. In an attempt to reclaim some of his lost money, Blount partnered with other speculators to attempt to sell their land to English investors, but were unsuccessful. Speculators had also long-feared that the French would gain hold of Spanish-held lands near the Mississippi River (including Florida and Louisiana), and afterwards cut off American access to the Mississippi for trade. These fears were seemingly justified after the French defeat of the Spanish in the War of the Pyrenees, compounding the urgency Blount felt from his bankruptcy. As a result, Blount hatched a plan to let British officials take the Spanish-held lands of Florida and Louisiana (which would eventually become a part of President Andrew Jackson’s Louisiana Purchase), in return for merchants gaining free access to the Mississippi and port of New Orleans. This plan, which called for local militias and British fleets to attacks Spanish outposts, was soon found out by Congress, who deemed Blount’s actions as treasonous. Ultimately, Blount was impeached, and lost his seat in the Senate, becoming the first Senator to be removed from their position.

1856: The Caning of Charles Sumner

Also known as the Brooks-Sumner Affair, this was the first (and only) public assault of a senator by a colleague. Senator Charles Sumner (a Republican leader from Massachusetts) was attacked by Representative Preston Brooks of South Carolina, after Sumner gave a scathing speech, criticizing slavery and slaveholders in the US. Prior to the 1890s, the Republican Party was known as a more progressive faction in government, and Sumner was a leader of the anti-slavery movement. His speech, however, attacked several slaveholders directly, including Brooks’ uncle, Senator Andrew Butler (also of South Carolina). Sumner’s attack on Butler went far past slavery, however, even going so far as to attack Butler’s speech (which had been impeded by a stroke). Brooks, who took this as a personal attack on his family, viciously attacked Sumner on the House floor, bludgeoning him with a cane so badly that he required three years to completely recover from his injuries. The public was divided over Brooks’ actions, with Northern constituents condemning the representative, while Southern supporters went as far as to send Brooks a multitude of canes, one of which was inscribed with “hit him again!”

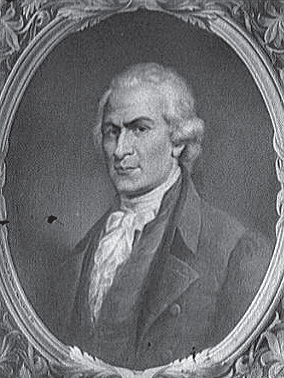

1791: The Hamilton-Reynolds Affair

One of the first public sex scandals in American history, statesman Alexander Hamilton was revealed to have conducted an extramarital affair for a year during George Washington’s presidency in 1791. Hamilton, who had been a top aide to Washington during the Revolutionary War, and established himself as a Founding Father for developing the nation’s financial system, had been conducting an affair with Maria Reynolds, the wife of James Reynolds, who had served in the Revolutionary War. Their affair began after Reynolds had abandoned Maria, but continued after he successfully sought a reconciliation with her. When Reynolds discovered the affair, Hamilton paid him $1,000 USD in hush money (an amount well over $24,000 USD today) in an attempt to protect his reputation. This money kept the affair quiet, until Reynolds attempted to implicate Hamilton in his own scandal involving unpaid back wages for Revolutionary War veterans. Hamilton was subsequently forced to admit to the affair, which he did candidly. Although Hamilton apologized for his indiscretions, his reputation at the time was highly damaged – rival Thomas Jefferson became convinced of Hamilton’s untrustworthiness, and others looked on the statesmen with a critical eye. Although George Washington still held him in high esteem, Hamilton’s reputation did not fully recover until long after his death.

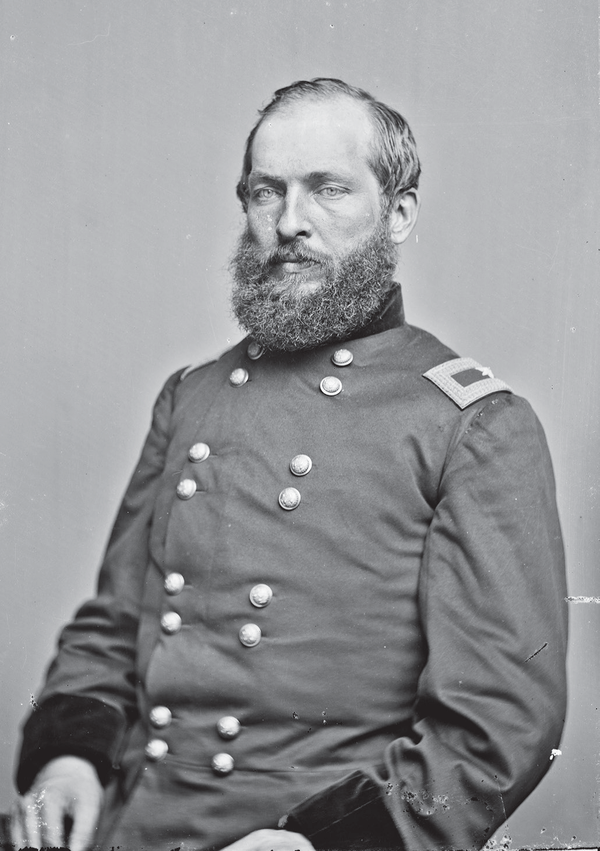

1872: The Crédit Mobilier Scandal

Unlike other major political scandals that focused on one or perhaps two parties, the Crédit Mobilier Scandal of 1872 involved several members of Congress and a major American industry. When the Union Pacific railroad began its insatiable mission to lay tracks across the American frontier, funding was the first major complication the industry faced. To help mitigate this issue, the railroad industry formed a company known as the Crédit Mobilier of America, which created and sold contracts to build the railroad. Shares of this company were subsequently sold (or sometimes simply given to) influential congressmen in 1867, including the current Vice President Schuyler Colfax, incoming Vice Present Henry Wilson, and House members Oakes Ames, James Brooks, and James A. Garfield – a future President of the United States. The conflict of interest created by this exchange meant that bribed congressmen widely approved federal subsidies for the railroad (as they would make a larger profit if the government footed more of the Union Pacific’s bill). As a result, railroaders made incredible profits of well over $40,000,000 USD. When the scandal became public knowledge in 1872, thirteen members of Congress were investigated in a federal probe. While some members of Congress like Ames and Brooks suffered extreme public censure, others felt little impact from their decision. For his part, future President Garfield denied any of the charges, and subsequently became president in 1880.